| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 1, January 2025, pages 39-46

Anticoagulation in Elderly Ischemic Stroke Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Perspective From a Tertiary Neuroscience Center

Shi Ying Tana, c , Ye Thwinb, Jessie Colacionb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Hospital, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

bDepartment of Neurology, Brunei Neuroscience Stroke & Rehabilitation Centre, Pantai Jerudong Specialist Centre, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

cCorresponding Author: Shi Ying Tan, Department of Internal Medicine, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Hospital, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

Manuscript submitted August 28, 2024, accepted December 30, 2024, published online January 8, 2025

Short title: Anticoagulation in Elderly Stroke Patients With AF

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr848

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Oral anticoagulation reduces the risk of cardioembolic (CE) stroke due to atrial fibrillation (AF). Despite guideline recommendations, anticoagulation use remains underutilized, especially in elderly patients.

Methods: This was a retrospective cross-sectional study to assess the oral anticoagulation use among elderly patients (≥ 65 years old) with AF-related CE strokes admitted to Brunei Neuroscience Stroke & Rehabilitation Centre (BNSRC) from January 2020 to December 2021. This study aimed to: 1) determine the incidence of AF-related CE stroke in the elderly; 2) describe the patients’ demographic and clinical profiles; 3) describe the pattern of anticoagulation use; and 4) describe the stroke recurrence, bleeding, and mortality within the 2 years follow-up. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0.

Results: Of all ischemic stroke patients admitted within the study period, 74 (23.8%) were elderly with AF-related CE stroke. The annual incidence of AF-related CE strokes in the elderly was 35.3% in 2020 and 22.3% in 2021. The median age was 77.0 years (interquartile range (IQR): 13.0) and 54.1% were males. The median CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.0, with hypertension (79.7%) being the most common co-morbidity. The majority (75.7%) received anticoagulation, mostly direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (89.3%), specifically dabigatran (62.5%). There were higher mortality (72.2%, P = 0.001) and bleeding (38.9%, P = 0.032) in non-anticoagulated patients. However, there was no significant stroke recurrence between the groups on DOACs, warfarin and no anticoagulation (P = 0.557). Subtherapeutic anticoagulation showed a higher trend but was not statistically significant in terms of mortality (42.9%, P = 0.165), bleeding (21.4%, P = 0.350), and stroke recurrence (14.3%, P = 0.590). Among patients ≥ 80 years of age, there was also no significant increase in bleeding, stroke recurrence, or mortality with anticoagulation.

Conclusion: There was a high incidence of CE ischemic strokes in elderly patients with AF in BNSRC, Brunei Darussalam. Majority of our patients received DOACs. Anticoagulated patients had lower bleeding and mortality risk.

Keywords: Anticoagulation; Cardioembolic stroke; Elderly; Old age; Atrial fibrillation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cardioembolic (CE) stroke is a debilitating disease with high mortality. It is mostly associated with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and its prevalence increases with age [1]. CE stroke secondary to AF has higher mortality, stroke recurrence, complications, and more severe disability compared to patients without underlying AF [2]. Oral anticoagulation therapy reduces the risk of CE stroke by up to 70% in patients with NVAF [1]. Anticoagulant use in CE stroke is a grade 1A recommendation according to the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guideline (2021) [3]. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is often used to estimate future stroke risk, and patients with a score of 2 or greater will benefit from anticoagulation usage [4]. Although bleeding risk also increases with age, it is not suggested that the elderly should avoid anticoagulation therapy. Furthermore, several studies have shown that older patients may still benefit from anticoagulation despite having more co-morbidities and poorer functional status [3, 5], and that patients with no therapy or suboptimal anticoagulation have higher bleeding risk, recurrent falls, and dementia [5]. The overall benefit of anticoagulation in the elderly outweighs its bleeding risk, hence patients who are 75 years or older are considered as high thromboembolic risk population and CHA2DS2-VASc score is even unnecessary/optional for therapy initiation [6]. If anticoagulation was to be initiated, data have shown that direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) is superior over vitamin K antagonist (VKA) in elderly patients [7]. However, despite evident recommendations, anticoagulation therapy remains underutilized, especially in elderly patients [2, 5, 6]. Currently, data on oral anticoagulation use in elderly patients in Brunei Darussalam remain sparse.

Aim and objectives

This study primarily aimed to assess the oral anticoagulation use among elderly patients with CE strokes related to AF who were admitted to Brunei Neuroscience Stroke & Rehabilitation Centre (BNSRC) from January 2020 to December 2021. Conventionally, an elderly patient is defined as chronological age of 65 or more [8, 9].

The objectives were to: 1) determine the incidence of elderly stroke patients with AF in BNSRC, Brunei Darussalam; 2) describe the demographic and clinical profiles of these patients; 3) describe the pattern of anticoagulation use; and 4) describe the stroke recurrence, bleeding risks, and mortality within 2 years follow-up.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design, population, and sample

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study of elderly stroke patients with AF admitted to BNSRC within January 1, 2020, until December 31, 2021. The sample population was obtained from the BNSRC’s neurology daily ward admission census within the period. Acute ischemic stroke patients aged ≥ 65 years, with AF and on oral anticoagulation, were included. Patients who passed away before oral anticoagulation therapy was started were excluded, including those who were on subcutaneous anticoagulation titration. A total of 74 patients were included in the study.

Data collection

Data on identified patients were extracted from the hospital’s medical information system, BRUHIMS. Personal patient identifiers were anonymized using assigned letter-digital codes in the database. The data collected were patient’s age during diagnosis, gender, stroke territory, parameters for CHA2DS2-VASc score (history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), vascular disorders history - previous myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease or aortic plaque, diabetes mellitus), albumin and creatinine levels, anticoagulant prescribed and their dosages. Adverse events, particularly bleeding complications and mortality within 2 years after initiation of anticoagulation, were recorded. Data of the patients were collated collectively and individual patient data would not be identifiable from the final analysis.

Research instruments

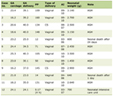

Table 1 is used to determine whether anticoagulation is adequate/therapeutic for patients [10, 11].

Click to view | Table 1. Anticoagulation Adequate/Therapeutic for Patients |

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. The incidence of CE strokes among elderly patients was calculated by the number of AF-related CE strokes divided by the total number of ischemic stroke admissions in elderly patients within the study period.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, and the types and doses of anticoagulation used were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The anticoagulation dosing was classified into appropriate (recommended dose) and inappropriate (under- and overdosed). Independent t-test for continuous, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were used to test for significance. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Comparisons of groups included: 1) composite anticoagulation with no anticoagulation; 2) DOACs versus warfarin versus no anticoagulation; 3) whether dosing of the anticoagulation for DOACs or therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) for warfarin group would affect their clinical outcome; 4) and whether patient’s age would affect their clinical outcomes (patients < 80 years and ≥ 80 years).

Ethical considerations

This study protocol was registered to Neuroscience Research Innovation Hub (NeuRIH) of BNSRC and Biomedical Research and Ethics Unit (BREU), Brunei Ministry of Health, and received ethical approval from Brunei Darussalam’s Medical Health Research and Ethics Committee (MHREC).

| Results | ▴Top |

The number of patients who were ≥ 65 years old with cerebrovascular events (either acute ischemic strokes or TIA) was 136 in 2020 and 175 in 2021. The incidence of CE strokes in elderly patients was 39.0% (n = 53) in 2020 and 31.4% (n = 55) in 2021, while the annual incidence of elderly CE strokes attributed from AF was 35.3% (n = 48) in 2020 and 22.9% (n = 40) in 2021. There were 14 inpatient CE stroke mortalities (13 with underlying AF), who were excluded from the final analysis, since anticoagulation was not yet started.

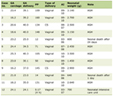

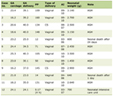

Of our patients, 54.1% were males, and the median age was 77.0 years. The median age of patients who were not anticoagulated was older (82.0 years old, P = 0.004). Hypertension (79.7%) was the most common co-morbidity. The overall median CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.0, but patients on warfarin had the highest median CHA2DS2-VASc score (6.5). Table 2 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of patients.

Click to view | Table 2. Demographics and Clinical Profiles of Elderly CE Stroke Patients With NVAF |

The majority (n = 56, 75.7%) of the AF-related elderly CE stroke patients received anticoagulation. Most of them were on DOAC, mainly 110 mg twice daily (BD) of dabigatran (Table 3). Three of the warfarin patients were switched to the appropriate apixaban dose at subsequent clinic visits (1 - 3 years after stroke). One patient was on dabigatran 110 mg once daily (OD), and switched to appropriate apixaban dose of 5 mg BD after a recurrent stroke. Of the patients on warfarin (n = 6, 10.7%), half had impaired renal function. In our study, 18 patients (24.3%) were not anticoagulated. The documented reasons for not giving anticoagulation were presence of hemorrhagic transformation or significant microbleeds on initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or subsequent follow-up computed tomography (CT) scans (n = 8, 44.4%), advanced age or frailty (n = 6, 33.3%), patients’ families refusing anticoagulation (n = 2, 11.1%), and presence of extracranial bleeding (n = 2, 11.1%).

Click to view | Table 3. Anticoagulation Used in CE Stroke Patients (n = 56) |

There were significant mortality (P = 0.001) and bleeding (P = 0.032) at 2 years follow-up in patients without anticoagulation (Table 4). Five patients who received anticoagulation had recurrent strokes within 2 years, while none was seen in those who did not receive anticoagulation. However, comparing DOACs, warfarin, and no anticoagulation, there was no significant stroke recurrence between the groups (P = 0.557) (Table 5).

Click to view | Table 4. Stroke Recurrence, Bleeding Risk, and Mortality Within 2 Years for Anticoagulation and Non-Anticoagulated Patients |

Click to view | Table 5. Comparisons of Outcomes Between DOACs, Warfarin, and Non-Anticoagulated Groups |

Of the patients, 55.4% (n = 31) received lower dosage of anticoagulation. When evaluated, 75% of our patients (n = 42) were prescribed appropriate doses as per guideline recommendations. Amongst the therapeutic and subtherapeutic groups who received anticoagulation, there was no statistical difference in terms of stroke recurrence, bleeding events, and mortality. However, there was a trend for poorer outcome with as much as twice increased incidence in stroke recurrence, bleeding events, and mortality rates amongst those who received subtherapeutic anticoagulation (Table 6).

Click to view | Table 6. Comparisons of Outcomes in Therapeutic and Subtherapeutic Dosage Groups |

A subgroup analysis of those super elderly patients (defined as aged ≥ 80 years old) was done. There were 29 patients (39.2%) who were within this age category with the median age of 84 years (IQR: 6.0) and 62.1% (n = 18) were males; 62.1% (n = 18) received anticoagulation, with mostly on dabigatran (n = 10, 55.6%), followed by apixaban (n = 6, 33.3%), and warfarin (n = 2, 11.1%). There were no significant rates for stroke recurrence (P = 0.652), bleeding (P = 1.000), and mortality (P = 1.000) between patients < 80 and ≥ 80 years old who received anticoagulation (Table 7).

Click to view | Table 7. Comparison Between Patients < 80 Years Old and ≥ 80 Years Old |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The relevance of studies on the elderly with CE strokes cannot be over-emphasized as they may often be vulnerable to undertreatment despite guideline recommendations. Among the 311 acute stroke admissions in 2020 - 2021, 74 (23.8%) were elderly patients with AF-related CE strokes. The proportions and prevalence of elderly stroke patients varied in different countries, from 12.0% in Taiwan [12] to 60.0% and 96.4% in Spain and northwestern China, respectively [13, 14]. In our cohort, the annual incidence of AF-related CE strokes in the elderly was 35.3% in 2020 and 22.3% in 2021. In comparison to studies which included stroke patients ≥ 65 years, our median age was similar to the mean age in Ljubljana (77.9 years) [15], as well as in Columbia and Puerto Rico (79.4 years) [16].

Of our elderly stroke patients, 75.7% were prescribed anticoagulation, comparable to studies done in Canada (73.0%) [17], Columbia and Puerto Rico (76.3-88.7%) [16], unlike those in Spain (40.9%) [13], Taiwan (26.7%) [12], and northwestern China (20.0%) [14]. Factors associated with lower anticoagulation use or not initiating anticoagulation are advanced age, presence of dementia, high falls risk, recent major bleeding, more severe stroke, patient refusal, and being in long-term care residences or palliative care [17, 18]. Despite the presence of dementia in elderly people being often associated with underuse of anticoagulation therapy, systemic reviews concluded that dementia risks were reduced as long as elderly AF patients were given anticoagulation [19]. Jacobs et al reported that patients on DOAC had a 51% decreased risk of dementia incidence or subsequent stroke or TIA compared with those taking warfarin (hazard ratio (HR) 0.49 (confidence interval (CI) 0.35, 0.69), P < 0.0001) [20]. DOACs may even prevent cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease by preserving vascular integrity and brain perfusion through inhibiting thrombin and its production [21].

Of our patients on anticoagulation, 89.3% were on DOACs. Use of DOACs in AF-related CE ischemic strokes is a class IA recommendation according to the AHA/ASA 2021 guidelines. For elderly stroke prevention, dabigatran was the most prescribed anticoagulation in Brunei, and a similar trend was seen in Ljubljana (66.1%) [15] and Korea (48.1%) [22], while apixaban was mostly prescribed in France (64.3%) [23]. Surprisingly, warfarin (19.4%) was more commonly prescribed in northwestern China and this was mainly due to cost issue [14]. Health care is fully subsidized by the Brunei government, including access to government registered DOACs. There were 10.7% of patients who were given warfarin in our study. They have the highest median CHA2DS2-VASc score (6.5), and 50.0% had impaired kidney function. Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD-Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF), a worldwide registry of patients with newly diagnosed AF from 35 countries, reported that in patients with permanent AF, kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, and vascular disease, warfarin and concurrent use of aspirin are the preferred choice [24].

Our study demonstrated that anticoagulation use resulted in significantly less death (P = 0.001) and less bleeding (P = 0.032) in elderly patients with AF-related CE ischemic strokes after 2 years of follow-up. In general, meta-analyses recommend DOAC use in elderly population. In elderly patients, recurrent stroke is less frequent in DOAC group compared to warfarin group, with a relative risk reduction of 20-30%. The general consensus showed that DOAC patients had statistically non-significant, but less major bleeding events and lower mortality [6]. It was noted that DOAC group had a 44% decreased risk of intracranial hemorrhage, but 46% increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, when compared with warfarin [25]. A study done in United States with CE stroke with AF in patients older than 65 years old showed that DOAC users had fewer deaths (P < 0.001), all-cause re-admissions (P = 0.003), less hemorrhagic strokes (P = 0.02), bleeding risk (P = 0.009), and more days at home (mean days 287.2) when compared with warfarin (mean days 263.0) [26]. When individually analyzed each DOAC in comparison with warfarin, dabigatran had overall more favorable outcomes, such as lower mortality, stroke, and intracranial hemorrhage, while apixaban had lower major bleeding risk. Rivaroxaban performed less satisfactory overall, having higher mortality and major bleeding risk [25].

The Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial compared two doses of dabigatran (150 mg BD and 110 mg BD) versus warfarin, and showed that both doses of dabigatran had lower risk of intracranial bleeding, regardless of age, but higher risk of extracranial bleeding for patients ≥ 75 years old. The reduced dose (110 mg) of dabigatran had lower risk of major bleeding, but showed similar efficacy for ischemic stroke prevention when compared to warfarin [27]. Similarly, apixaban 5 mg BD (ARISTOTLE trial) showed overall reduction of stroke, primarily intracranial hemorrhage, and lower risk of major bleeding and mortality [28]. While comparing rivaroxaban 20 mg OD with warfarin (ROCKET-AF trial), rivaroxaban displayed reduction in intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding, but no significant difference in terms of major bleeding or stroke reduction [29]. Dabigatran 150 mg BD is the only DOAC that demonstrated clinical benefit of lower ischemic stroke rates [27]. However, it is important to note that elderly patients ≥ 75 years old only constituted 31-40% of the three large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [27-29]. A meta-analysis involving five phase-III RCTs (ARISTOTLE, ENGAGE AF-TIMI48, Japanese-ROCKET AF (J-ROCKET AF), RE-LY, and ROCKET AF) demonstrated that standard-dose DOAC had better efficacy in patients who were ≥ 75 years when compared to warfarin, except higher tendency of GI bleeding, whereas low-dose DOACs showed equivalent efficacy compared to warfarin [30].

Our study failed to demonstrate a statistical advantage of giving anticoagulation over no anticoagulation in preventing stroke recurrence in 2 years. This may be related to sampling bias as only 75.7% of patients were given anticoagulation. Furthermore, therapeutic advantage of those on anticoagulation may not be as robust as only about 75.0% on anticoagulation were on appropriate doses (including therapeutic INRs) after individual dose adjustments. Seiffge et al also reported that stroke patients had higher recurrent risks despite anticoagulation, possibly due to competing stroke risk factors and etiologies, such as large artery atherosclerosis or small vessel disease [31]. Indeed, five of our recurrent stroke patients on anticoagulation had documented intracranial or extracranial disease in the same vascular territory, which implied that the recurrence cause was not CE, but artery-artery embolic or thrombotic cause, which would not have responded to anticoagulation. Reviewing the imaging of the five patients who had stroke recurrences, significant intracranial and extracranial disease on the side of the stroke recurrence as well as microangiopathic disease was confirmed. Another possible reason may be due to non-compliance of medication, as dabigatran and apixaban are both twice daily dosing. Once daily DOACs such as rivaroxaban or edoxaban can be an option, although rivaroxaban generally had less favorable outcomes, and higher failure rates compared to other DOACs [25, 32]. In addition, underdosing of DOAC therapy, which is commonly seen in Asian population, may result in treatment failure [6, 32]. It is a common clinical practice to prescribe lower doses to prevent bleeding in elderly patients [18]. Drug interactions, particularly cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers, may also result in subtherapeutic treatment [32].

Comparison between therapeutic (appropriate) and subtherapeutic doses of anticoagulation in preventing stroke recurrence, death, and bleeding propensity did not reveal significant difference. This indicates that there might be no advantage in giving subtherapeutic doses to prevent bleeding, which is often the indicated cause for reduced dosing. Additionally, this study also demonstrated a non-statistically significant trend for worse outcome with subtherapeutic dosing, with about doubled incidence of stroke recurrence, bleeding, and mortality per subgroup. Of our patients, 55.4% (n = 31) received lower dosages of anticoagulation. The trend of lowering anticoagulation dosage was seen in multiple other studies, where reduced doses were reported in up to 87.5% of the study population [15, 18, 33]. Age is one of the factors for dose reduction, as per guideline recommendation. However, eliminating the age factor, low dosage was inappropriately prescribed in 25.0% of patients in Italy [33]. The trend was also seen in our study, where 25.0% of patients received inappropriate anticoagulation dosage.

Our study observed that patients ≥ 80 years old did not have worse outcomes in terms of mortality, bleeding risk, and recurrent stroke risk. A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan found that patients with AF ≥ 90 years old had reduced risk of ischemic stroke with anticoagulants, whether warfarin or DOACs, but the latter was associated with lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage, making it a preferable choice in the elderly [34]. This was supported by a Swedish study comparing AF patients with recent ischemic stroke in three different groups: 80 - 84 years, 85 - 89 years, and ≥ 90 years, and concluded that anticoagulation reduced mortality and stroke risk in all three groups. The age group of ≥ 90 years had the highest hemorrhages risk, but the overall beneficial outcome outweighed the risk [35]. Polymeris et al concurred that DOAC had similar net clinical benefit regardless of age (comparing patients < 85 years and ≥ 85 years) [7]. On the contrary, a study in Okayama, Japan preferred warfarin use for ultra-aged (≥ 90 years) patients with AF. In the study, DOAC had more major bleeding events, whereas no anticoagulation had higher thromboembolic events. Warfarin achieved the balance in which it reduced all-cause mortality and had acceptable incidence of both thromboembolic and major bleeding events [36]. Similarly, Giustozzi et al observed that patients ≥ 90 years old with AF in Italy had numerically more major bleeding events in DOACs but non-statistically significant when compared to warfarin [18].

Anticoagulation use in the elderly is complex, as this population has greater co-morbidities, frailty, polypharmacy, psychosocial issues, and bleeding risks. However, age, dementia, or falls should not be deterring factors of anticoagulation. Guidelines recommend DOAC as a preferred option for elderly population as the benefits outweigh the risks, and net clinical benefit is greater in standard doses. Anticoagulation may even have a beneficial role in decreasing cognitive impairment. For patients with frequent falls, apixaban and edoxaban are a superior choice compared to warfarin. A patient-based comprehensive geriatric assessment is recommended prior to initiating anticoagulation treatment [37].

One of the limitations of this study was the small study which could diminish the effect size of the measured variables. Additionally, data were based on retrospective analysis and possible unmeasured confounders could affect the analysis. In addition, being institutional based may have resulted in collection bias; despite BNSRC being the sole tertiary neurology service, some patients with other co-morbidities or coronavirus positive may not be admitted under neurology during the pandemic period. Lastly, a small sample size, as well as classifying all bleeding risks into one category, could skew the final results.

In conclusion, our study reinforced that elderly patients, even when ≥ 80 years old, do not have worse outcomes, and should be anticoagulated with appropriate dosing. DOACs have better efficacy and equivalent safety when compared to warfarin for elderly stroke patients. Further studies with greater sample size including other hospitals are warranted.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

This study had sought for a waiver of patients’ consent in view of a retrospective study, in which the researcher will not be in any form of direct contact with the participants involved in the study. The research involves no more than minimal risk to subjects, and the waiver will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the patients.

Author Contributions

Shi Ying Tan is responsible for study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. Ye Thwin is responsible for data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, while Jessie Colacion is responsible for study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Data Availability

All data collected will remain under BNSRC and Ministry of Health, Brunei Darussalam.

Abbreviations

AF: atrial fibrillation; BD: twice daily; BNSRC: Brunei Neuroscience Stroke & Rehabilitation Centre; CE: cardioembolic; DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; IBM SPSS: IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; INR: international normalized ratio; OD: once daily; TIA: transient ischemic attack

| References | ▴Top |

- Jurjans K, Vikmane B, Vetra J, Miglane E, Kalejs O, Priede Z, Millers A. Is anticoagulation necessary for severely disabled cardioembolic stroke survivors? Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(9):586.

doi pubmed - Sur NB, Wang K, Di Tullio MR, Gutierrez CM, Dong C, Koch S, Gardener H, et al. Disparities and temporal trends in the use of anticoagulation in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2019;50(6):1452-1459.

doi pubmed - Bushnell CD, Colon-Emeric CS. Secondary stroke prevention strategies for the oldest patients: possibilities and challenges. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(3):209-230.

doi pubmed - Gorczyca I, Jelonek O, Michalska A, Chrapek M, Walek P, Wozakowska-Kaplon B. Stroke prevention and guideline adherent antithrombotic treatment in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A real-world experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(29):e21209.

doi pubmed - Bo M, Grisoglio E, Brunetti E, Falcone Y, Marchionni N. Oral anticoagulant therapy for older patients with atrial fibrillation: a review of current evidence. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;41:18-27.

doi pubmed - Deltour S, Pautas E. Anticoagulation decisions in elderly patients with stroke. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2020;176(9):692-700.

doi pubmed - Polymeris AA, Macha K, Paciaroni M, Wilson D, Koga M, Cappellari M, Schaedelin S, et al. Oral anticoagulants in the oldest old with recent stroke and atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(1):78-88.

doi pubmed - Singh S, Bajorek B. Defining 'elderly' in clinical practice guidelines for pharmacotherapy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):489.

doi pubmed - Improving care for older people: NHS England. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/older-people/improving-care-for-older-people/.

- Dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta249.

- Wigle P, Hein B, Bernheisel CR. Anticoagulation: updated guidelines for outpatient management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(7):426-434.

pubmed - Lin Y-J, Po HL. Use of oral anticoagulant for secondary prevention of stroke in very elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: an observational study. International Journal of Gerontology. 2011;5(1):45-48.

- Benavente L, Calleja S, de la Vega V, Garcia J, Lahoz CH. Oral anticoagulation in elderly patients as secondary prevention of cardioembolic strokes. Int Arch Med. 2010;3:8.

doi pubmed - Zhang J, Yang XA, Zhang Y, Wei JY, Yang F, Gao H, Jiao WW, et al. Oral anticoagulant use in atrial fibrillation-associated ischemic stroke: a retrospective, multicenter survey in Northwestern China. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(1):125-131.

doi pubmed - Frol S, Sernec LP, Hudnik LK, Sabovic M, Oblak JP. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in the secondary stroke prevention of elderly patients: Ljubljana registry of secondary stroke prevention. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(11):1053-1061.

doi pubmed - Lichtman JH, Naert L, Allen NB, Watanabe E, Jones SB, Barry LC, Bravata DM, et al. Use of antithrombotic medications among elderly ischemic stroke patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(1):30-38.

doi pubmed - Shah R, Li S, Stamplecoski M, Kapral MK. Low use of oral anticoagulant prescribing for secondary stroke prevention: results from the Ontario stroke registry. Med Care. 2016;54(10):907-912.

doi pubmed - Giustozzi M, Vedovati MC, Verso M, Scrucca L, Conti S, Verdecchia P, Bogliari G, et al. Patients aged 90 years or older with atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulants: A multicentre observational study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;281:56-61.

doi pubmed - Mongkhon P, Naser AY, Fanning L, Tse G, Lau WCY, Wong ICK, Kongkaew C. Oral anticoagulants and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;96:1-9.

doi pubmed - Jacobs V, May HT, Bair TL, Crandall BG, Cutler MJ, Day JD, Mallender C, et al. Long-term population-based cerebral ischemic event and cognitive outcomes of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin among long-term anticoagulated patients for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(2):210-214.

doi pubmed - Grossmann K. Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) for therapeutic targeting of thrombin, a key mediator of cerebrovascular and neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10(8):1890.

doi pubmed - Han S, Jeong HS, Kim H, Suh HS. The treatment pattern and adherence to direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation aged over 65. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214666.

doi pubmed - Azzoug C, Nuemi G, Menu D, De Maistre E, Boulin M, Putot A, Manckoundia P. Direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists in individuals aged 80 years and older: an overview in 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1448.

doi pubmed - Haas S, Camm AJ, Bassand JP, Angchaisuksiri P, Cools F, Corbalan R, Gibbs H, et al. Predictors of NOAC versus VKA use for stroke prevention in patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: Results from GARFIELD-AF. Am Heart J. 2019;213:35-46.

doi pubmed - Mitchell A, Watson MC, Welsh T, McGrogan A. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists for people aged 75 years and over with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):554.

doi pubmed - Xian Y, Xu H, O'Brien EC, Shah S, Thomas L, Pencina MJ, Fonarow GC, et al. Clinical effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin in older patients with atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke: findings from the patient-centered research into outcomes stroke patients prefer and effectiveness research (PROSPER) study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1192-1202.

doi pubmed - Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Healey JS, Oldgren J, Yang S, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation. 2011;123(21):2363-2372.

doi pubmed - Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992.

doi pubmed - Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891.

doi pubmed - Kim IS, Kim HJ, Kim TH, Uhm JS, Joung B, Lee MH, Pak HN. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants have better efficacy and equivalent safety compared to warfarin in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiol. 2018;72(2):105-112.

doi pubmed - Seiffge DJ, De Marchis GM, Koga M, Paciaroni M, Wilson D, Cappellari M, Macha Md K, et al. Ischemic stroke despite oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol. 2020;87(5):677-687.

doi pubmed - Bang OY, Park KM, Jeong DS. Occurrence of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants: causes and prevention strategies. J Stroke. 2023;25(2):199-213.

doi pubmed - Vannucchi V, Moroni F, Grifoni E, Marcucci R, Landini G, Prisco D, Masotti L. Management of oral anticoagulation in very old patients with non valvular atrial fibrillation related acute ischemic stroke. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49(1):86-93.

doi pubmed - Chao TF, Liu CJ, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Tuan TC, et al. Oral anticoagulation in very elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2018;138(1):37-47.

doi pubmed - Appelros P, Farahmand B, Terent A, Asberg S. To treat or not to treat: anticoagulants as secondary preventives to the oldest old with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2017;48(6):1617-1623.

doi pubmed - Yamaji H, Higashiya S, Murakami T, Hina K, Kawamura H, Murakami M, Kamikawa S, et al. Effects of oral anticoagulants on patients with atrial fibrillation aged 90 years and older: comparison among direct oral anticoagulant, warfarin anticoagulant, and nonanticoagulation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2019;74(3):246-254.

doi pubmed - Bonanad C, Formiga F, Anguita M, Petidier R, Gullon A. Oral anticoagulant use and appropriateness in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in complex clinical conditions: ACONVENIENCE study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7423.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.