| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 2, March 2025, pages 77-82

The Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic on Vertigo: Changes in Emergency Department Admissions and Management

Franco Cominottoa, Paola Carusob, c, Ugo Giulio Sistoa, Francesco Biaduzzinib, Carlo Lugnanb, Gabriele Prandinb, Magda Quagliottob, Paolo Manganottib

aEmergency Department, University Hospital and Health Services of Trieste, 34149 Trieste, Italy

bClinical Unit of Neurology, Department of Medicine Surgery and Health Sciences, ASUGI, University of Trieste, 34149 Trieste, Italy

cCorresponding Author: Paola Caruso, Clinical Unit of Neurology, Department of Medicine Surgery and Health Sciences, ASUGI, University of Trieste, 34149 Trieste, Italy

Manuscript submitted September 12, 2024, accepted December 30, 2024, published online January 17, 2025

Short title: Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Vertigo

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr850

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic brought several changes in the management of various pathologies, including vertigo. Dizziness and vertigo are usually responsible for approximately 5% of unselected presentations to emergency department (ED) or outpatient clinics. During the pandemic, a lower number of ED admissions for many pathologies has been reported. We aimed to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on vertigo management during the lockdown period.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of patients admitted for vertigo between January 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020, and compared them with those of patients admitted during the same time span in 2019. We compared the whole number of vertigo cases admitted in the first months of 2019 and 2020, respectively, and the number of admissions per week; we also reported the length of stay in the ED and the number of specialistic/radiological evaluations performed.

Results: We isolated 412 patients admitted to the ED of Cattinara Hospital, University of Trieste, from January to April 2019, compared to 303 patients admitted during the same period in 2020 (lockdown period). The two groups (group A and group B) were comparable in terms of age and gender. We found a decrease in ED admission during the intensive lockdown period when comparing the ED accesses in 2019 and 2020 (weeks 10 - 17: 23% (2019) vs. 9% (2020); P = 0.000898913).

Conclusions: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of vertigo cases, similar to those of stroke or cardiac pathologies, decreased. We also found a relative increase in admissions for central vertigo in our sample during the lockdown period, as well as an increase of “pseudo-vertigo”.

Keywords: COVID-19; Emergency department; Vertigo and dizziness; Neurological involvement; Pseudo-vertigo

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Recently, the majority of countries have experienced lockdown or restricted movement due to self-imposed or enforced quarantine as a result of the ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The global emergency has led healthcare systems to focus primarily on COVID-19 management. Moreover, most of the citizens are focused on COVID-19 symptoms and experienced widespread fear of accessing hospitals during the pandemic, resulting in a lower number of emergency department (ED) admissions for different other pathologies, such as transient ischemic attack, minor strokes, vertigo or cardiac pain [2]. Dizziness and vertigo are responsible for approximately 5% of unselected presentations to the ED or outpatient clinics, and among all major symptoms, dizziness is regarded as the third most common in general medical practice [3, 4]. Vertigo results from an imbalance in the tonic discharges of the vestibular system, which arises from the inner ears on both sides. The origin of vertigo may be peripheral or central. Vertigo prevalence is estimated to be 1.8% among young adults and above 30% in the elderly, so it accounts for up to 38% of the referrals of patients over age 65 in the USA [5]. Dizziness and vertigo, also associated with presyncope or a feeling of unsteadiness, account for almost 10 million outpatient visits per year in the USA, and approximately one-fourth of these patients are admitted to the ED [5]. When a patient is admitted for vertigo, the underlying pathology can be serious, for example a vestibular stroke can be missed at initial evaluation [6]. Stroke has been reported to account for 0.7-3.2% of dizziness cases in ED patients with dizziness [7]. Etiology of vertigo can be various, spreading from central vascular causes (stroke, hemorrhage), vasovagal syncope or orthostatic hypotension, to vestibular causes, electrolyte/glycemic disorders, circulatory/pulmonary causes (vertigo due to other different causes), as well as psychosomatic disorders, migraine or intoxication and substance withdrawal (also called “pseudo-vertigo”) [8]. Specialistic evaluation (neurological and/or otolaryngologic examination) and neuroimaging (computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain) are commonly used in the diagnostic workup of acutely dizzy patients presenting to the ED.

Moreover, vertigo has significant health care costs that include charges of the medications, laboratory, and imaging tests; varied health care costs between hospitalized and outpatients with dizziness have been documented. Accurate disease management may contribute to allocating medical resources efficiently, and thoughtful multidisciplinary work may alleviate the economic burden of these patients [9].

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemics on vertigo incidence in the ED and vertigo management. This report described the ED admissions for vertigo during the pandemic era and compared clinical features and outcomes of admitted patients between January 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020, with patients admitted during the same period in 2019. We compared the whole number of vertigo cases admitted in the first months of 2019 and 2020, respectively, and the number of accesses per week; we also reported the length of stay in the ED and the number of specialistic/radiological evaluation performed.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This retrospective study was conducted on patients admitted to the ED of the University Medical Hospital of Trieste between January 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020 (COVID-19 period), and the same period in 2019 (January 1, 2019, and April 30, 2019: no-COVID-19 period). We included all patients admitted to the ED with first symptom “vertigo”; data were extracted by using “vertigo” as the sorting key for the TRIAGE diagnosis in our “SEI” software, after all, we isolated the population related to the months from January to April per each year (2019 and 2020). Patients’ data were integrated analyzing all clinical information contained in the informatics archive of the hospital (G2 software): first aid reports, specialistic evaluation (neurological and otolaryngologic), and neuroimaging assessment (brain CT scan or brain MRI). For all patients, the following data have been described: 1) population data and demographic characteristics (age, gender, ED color code, vital parameters: blood pressure, body temperature, cardiac frequency rhythmic/arrhythmic, arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)); 2) length of stay in the ED; 3) number of consultations (otolaryngologic or neurological evaluation) and number of instrumental exams (neuroimaging); 4) history of vertigo: vestibular symptoms, neurological, pseudo-vertigo causes (ear pain, hearing loss, tinnitus, headache, nausea, vomiting, neck pain, lipotimia, syncope, trauma, dyspnea, heart disease), duration of vertigo, orthostatic hypotension maneuvers +/-; 5) signs evaluated by physicians: presence of nystagmus, spontaneous/provoked by maneuvers, gait disorders (latero/instinct or retropulsion), dysmetria, Romberg, cranial nerves involvement, presence of harmonic/disharmonic syndrome; 6) the class of diagnosis of vertigo (peripheral, central, others). Any information that was not reported in the first aid report and consultation was considered “not reported (NR)”, as the absence of a report does not indicate that it was a negative outcome.

We excluded patients whose TRIAGE findings did not include vertigo as the first diagnosis. Other exclusion criteria included the lack of ED report, lack of informed consent, and operating system errors (inability to find the patient). The specialist evaluation and instrumental diagnostics were included in the database if carried out during the recovery in the ED; follow-up and subsequent visits were not considered.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee CEUR (Comitato Etico Regionale FVG, Italy) with approval numbers 115/2018 and 039_2020H. The research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software for Windows (v21.0; IBM, Armonk, New York). Individual and aggregate data were summarized using descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviations, medians (minimum - maximum), frequency distributions, and percentages. Differences between the two groups were tested with the appropriate nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney U test). P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

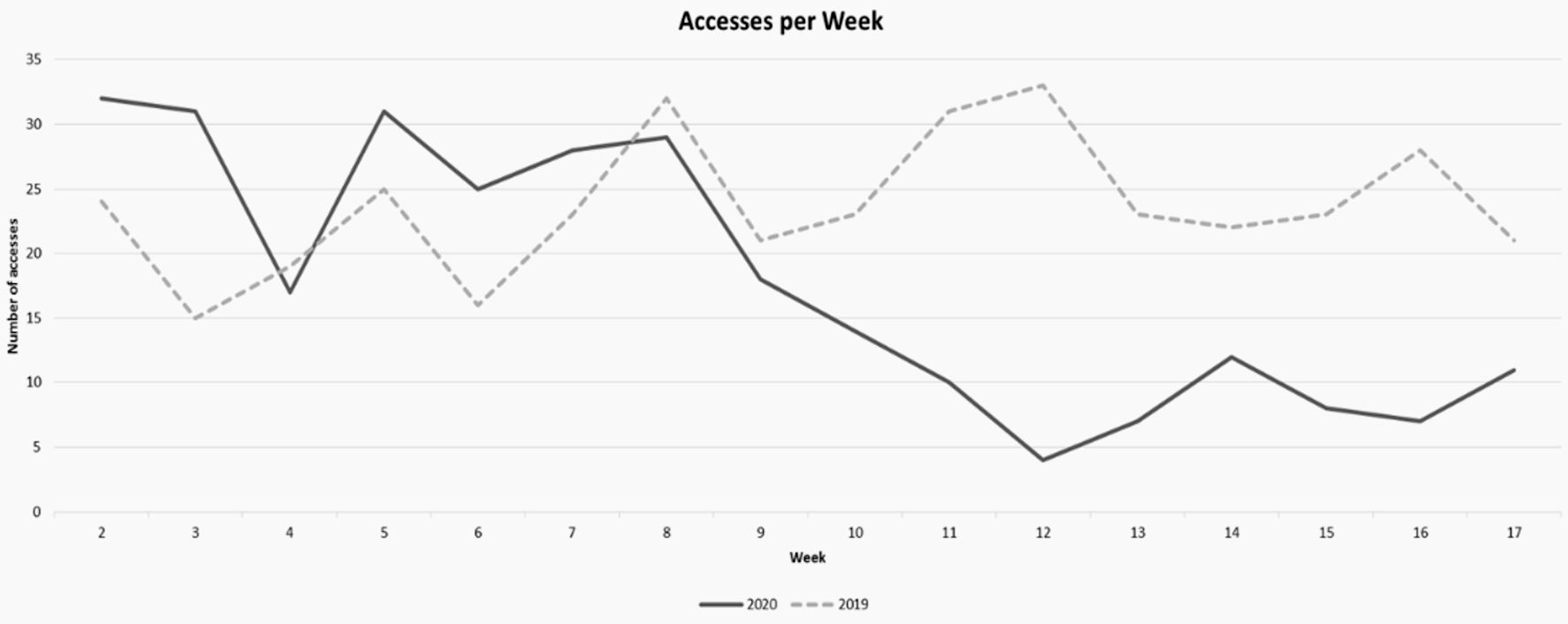

All patients admitted to the ED of the University Medical Hospital of Trieste between January 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020 (COVID-19 period), and the same period in 2019 (no-COVID-19 period) have been recruited. In the majority of cases, for both years, patients were admitted in the ED with a green code. We found 412 patients in 2019 (group A) versus 303 patients in 2020 (group B); considering accesses per week, we found a significant decrease in ED admission during the intensive lockdown period by comparing the ED accesses in 2019 and 2020 (P value = 0.0008 (weeks 2 - 9: 22% (group A) vs. 28% (group B); weeks 10 - 17: 23% (group A) vs. 9% (group B)). The first and 18th week were excluded from the statistical analysis because they were not comparable for numbers of days (Fig. 1). Patients in the two groups presented the same mean age (64 (49 - 76) group A, 63 (48 - 77) group B), female sex was prevalent in both sets (285 (69.2%) female/127 (30.8%) male for group A, and 206 (68%) female/97 (32%) male for group B) (Table 1). Analysis of vital parameters showed normal values in almost all cases in both groups (blood pressure, body temperature, cardiac frequency (usually rhythmic), SaO2 and FiO2). In a very few cases, blood pressure was high at admission (systolic peak > 180 - 200 mm Hg: 2% in 2019 vs. 4% in 2020).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Decreases in ED admission during the intensive lockdown period: comparison of ED accesses (2019 vs. 2020: weeks 10 - 17: 23% (2019) vs. 9% (2020); P = 0.000898913). ED: emergency department. |

Click to view | Table 1. Demographic Data |

All the patients analyzed were admitted for the symptom “vertigo”. In addition to this symptom, the majority of patients presented nausea (46.4% and 43.6%, respectively), vomiting, and headache (from 20% to 25% and 12% to 19%, respectively) as main symptoms; all other symptoms are reported in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 2. Other Symptoms Identified in Patients Admitted in the ED With Main Symptom “Vertigo” and Signs Detected on Neurological Examination |

In most cases otolaryngology consultation was performed (otorhinolaryngological (ORL) evaluation: 49% in group A vs. 39% in group B; neurological evaluation: 36% in group A vs. 19% in group B), and harmonic syndrome was found in 13% of cases in 2019 compared to 6% in 2020. Nystagmus was reported in 98 patients in group A (62 provoked, 30 spontaneous) and 78 patients in group B (42 provoked, 36 spontaneous). Gait disorders and other neurological or ORL deficits are reported in Table 2 (in most cases nystagmus and disequilibrium were found).

Almost 39% of patients underwent neuroimaging examination (brain CT scan for the majority, less than 1% for brain MRI) in both years; neuroimaging was positive in 2% of cases in group A and 6% of cases in group B.

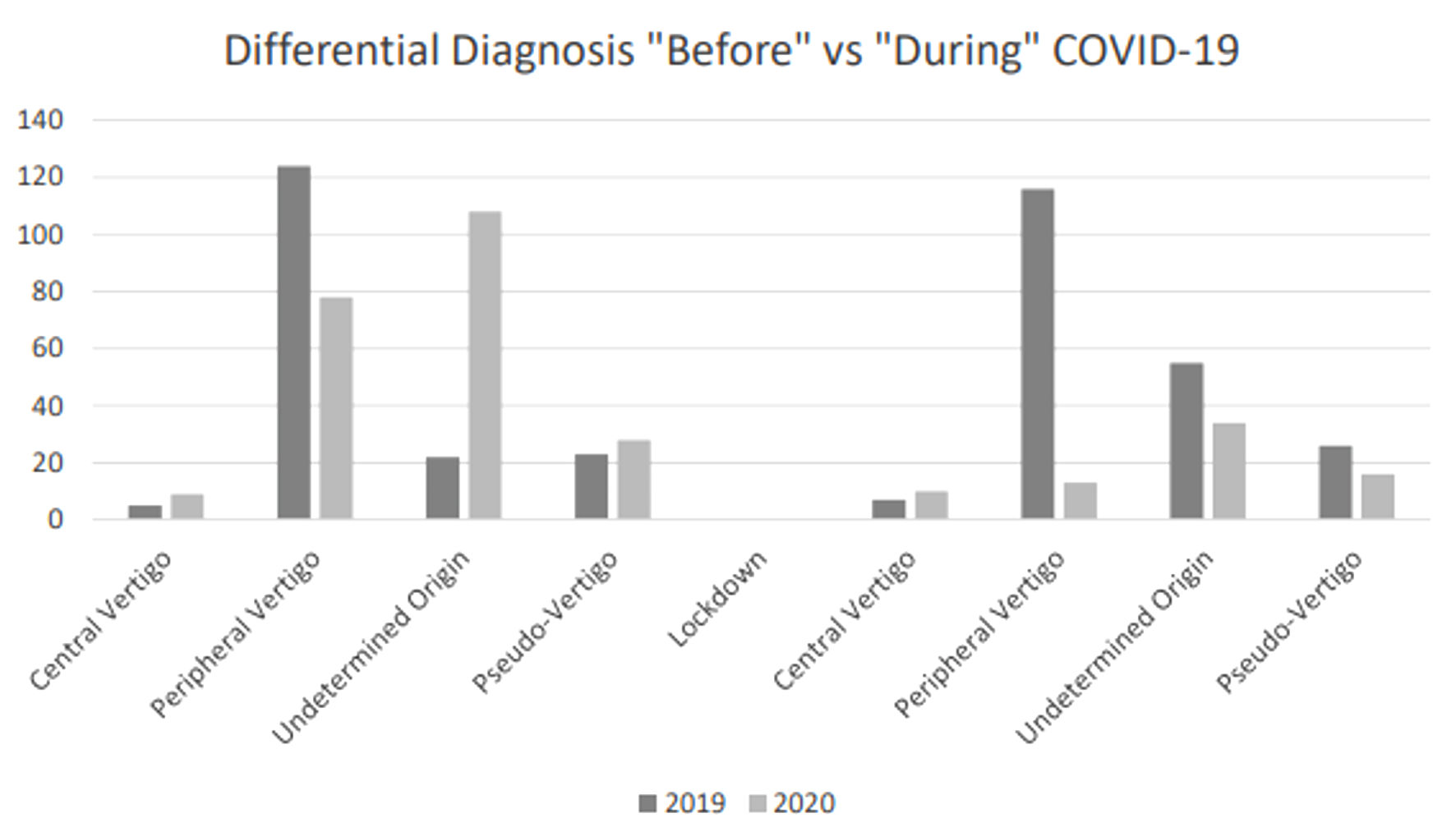

Vertigo due to central nervous system disease was found in 3.43% of patients in group A vs. 13.7% in group B (post lock-down); peripheral vertigo was diagnosed in 56.8% vs. 17.8% (group A and B, respectively, post lock-down). The other vertigos were defined as pseudo-vertigo, in 12.7% and 21.9% of cases, respectively (post lock-down) (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Differential diagnosis “before” vs. “during” COVID-19. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019. |

The median length of stay in the ED was about 6 h in 2019, compared to 5 h in 2020 (6.21 h vs. 4.43 h). Vertigo management has not changed. There has not been a significant variation in the number of specialistic consultations or radiological examinations carried out between the two periods under examination.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The main finding of our investigation is a reduction of total admissions in the ED of patients with vertigo during the first months of 2020, compared to the same period in 2019. This may be explained with the lower number of ED admissions for minor pathologies and slight neurovegetative symptoms, probably related to the diffused fear of going to the hospital during the pandemic. Indeed, during the state of emergency due to COVID-19, the attention of healthcare providers and health authorities has been primarily focused on infected patients. Moreover, most of the citizens focused on pandemic symptoms and were worried about accessing hospitals during this period. Remarkably, we found a higher number of central vertigos admitted as a green code in the lockdown era compared to 2019, probably showing what has been said before. Our data showed an increasing percentage of central vertigo, which might be explained by the following factors: most peripheral vertigo cases resolved in the first hours of observation in ED, so that the ED physician tried to anticipate the discharge at home, avoiding prolonging the patient’s stay in an area at risk of contagion (deferred neurological visit); many peripheral vertigo did not show up in the ED, and the increase in central vertigo rate does not reflect a significant statistical difference. We believe that, during the pandemic period, the reduction in request for neurological assessments can be explained by the adoption of faster therapeutic diagnostic paths in the ED, which required neurological evaluation only for vertigo of probable central origin. In 2020, there was an increase in the number of vertigo cases due to other different causes, including “pseudo-vertigo” and anxiety disorders. These data lead to two main considerations: first, the finding of an increase in central vertigo cases reflects the indecision of the patient with mild neurological symptoms (particularly when referring to mild gait disorders or stability deficits) to present to the ED quickly during a pandemic; second, there may have been an increase in anxiety and somatization disorders as a defense against lockdown itself.

Vertigo is the illusion of true rotational movement of oneself or the surroundings and is a frequent complaint of patients presenting to the ED. It is frequently associated with the presence of nystagmus and is most likely due to vestibular system dysfunction [10, 11]. Patients complaining of vertigo often also experience imbalance or disequilibrium, described as a sense of unsteadiness, often indistinguishable by patients, and commonly by physicians, from true vertigo. Many other symptoms like dizziness and a variety of disorders, not necessarily vestibular in nature, such as presyncope (hyperventilation, orthostatic hypotension, vasovagal attacks, decreased cardiac output), anxiety disorders (panic syndrome, agoraphobia), hypoglycemia and drug intoxication (alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepine), can be described (conditions defined as “pseudo-vertigo”). The most common causes of dizziness and vertigo are benign; however, differential diagnoses include potentially life-threatening central diseases, as vertigo can be the manifestation of central neurological disease, such as cerebellar or brainstem stroke. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most common form of positional vertigo, whose incidence increases with age. It is the most frequent cause of isolated vertigo, and the recurrence is estimated in 36% of cases [12, 13].

This study has several limitations. First of all, data have been collected retrospectively. Moreover, our work has been limited by the impossibility in collecting all data due to operating system errors or lack of informed consent; and it was not often possible to know if the anamnestic or clinical data not reported by the doctors had been investigated or not. Finally, the protocol used in the ED at the time of the study did not include all the clinical signs (e.g., head impulse test), which are usually performed by specialistic evaluation. Recently, we applied the STANDING Algorithm to select central and peripheral vertigo according to the most recent data [14].

Conclusions

In our experience, and according to the literature, diagnosing patients with dizziness is challenging, and ED physicians often request neurological consultation and brain imaging studies to differentiate non-vestibular medical causes from peripheral or central vestibular disorders [15-17]. During the COVID-19 era, the number of patients admitted to the ED for conditions other than respiratory syndrome sharply dropped. The number of vertigo cases has decreased, similar to what has been observed for stroke and cardiac pathologies. We also found an increase in central vertigo cases in our sample during the lockdown period. These data are concerning because they reflect a delay in patients seeking medical care. On the other hand, we report an increase in “peudo-vertigo”, during the same period, due to an increasing discomfort/fear in the population and an intensification of somatization disorders, likely related to the pandemic.

In the ED, physicians collaborate daily with specialists (such as neurologists and otolaryngologists) to better frame the dizzying symptoms complained of by the patient in a short time. We believe that correct information is fundamental for the patient; in particular, a perceived recognition of symptoms that could be linked to central neurological pathology should promptly push the patient to a medical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable because this is a retrospective study conducted on the consultation of a database.

Author Contributions

FC: conceptualization, validation. PC: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, validation, visualization, writing - original draft. UGS: conceptualization, data curation. FB: conceptualization, data curation. CL: conceptualization, data curation. GP: conceptualization, data curation. MQ: visualization, writing - review and editing. PM: funding acquisition, validation, visualization, writing - review and editing.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Caso V, Federico A. No lockdown for neurological diseases during COVID19 pandemic infection. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(5):999-1001.

doi pubmed - Naccarato M, Scali I, Olivo S, Ajcevic M, Buoite Stella A, Furlanis G, Lugnan C, et al. Has COVID-19 played an unexpected "stroke" on the chain of survival? J Neurol Sci. 2020;414:116889.

doi pubmed - Kroenke K, Jackson JL. Outcome in general medical patients presenting with common symptoms: a prospective study with a 2-week and a 3-month follow-up. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):398-403.

doi pubmed - Newman-Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, Rothman RE, Hsieh YH, Zee DS. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: a cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(11):1329-1340.

doi pubmed - Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011;183(9):E571-592.

doi pubmed - Kerber KA, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Smith MA, Morgenstern LB. Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department: a population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2484-2487.

doi pubmed - Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, Brown DL, Burke JF, Hofer TP, Tsodikov A, Hoeffner EG, et al. Stroke risk stratification in acute dizziness presentations: A prospective imaging-based study. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1869-1878.

doi pubmed - Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Jr., Pelletier AJ, Butchy GT, Edlow JA. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(7):765-775.

doi pubmed - Saber Tehrani AS, Coughlan D, Hsieh YH, Mantokoudis G, Korley FK, Kerber KA, Frick KD, et al. Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):689-696.

doi pubmed - Herr RD, Zun L, Mathews JJ. A directed approach to the dizzy patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(6):664-672.

doi pubmed - Armato E, Ferri E, Pinzani A, Ulmer E. Cerebellar haemorrhage mimicking acute peripheral vestibulopathy: the role of the video head impulse test in differential diagnosis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(4):288-291.

pubmed - Casani AP, Dallan I, Cerchiai N, Lenzi R, Cosottini M, Sellari-Franceschini S. Cerebellar infarctions mimicking acute peripheral vertigo: how to avoid misdiagnosis? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(3):475-481.

doi pubmed - Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, Chalian AA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(5 Suppl 4):S47-81.

doi pubmed - Vanni S, Pecci R, Edlow JA, Nazerian P, Santimone R, Pepe G, Moretti M, et al. Differential diagnosis of vertigo in the emergency department: a prospective validation study of the STANDING algorithm. Front Neurol. 2017;8:590.

doi pubmed - Helmchen C, Machner B, Lehnen N, Jahn K, Schneider E, Sprenger A. Current state of diagnostic management of acute vertigo: a survey of neurologists in Germany. J Neurol. 2014;261(8):1638-1640.

doi pubmed - Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Giles MF, Elkins JS, Bernstein AL, Sidney S. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

doi pubmed - Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, Grossman AW, Wong C, Poisson SN, Whetstone WD, et al. Rate and predictors of serious neurologic causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(11):1080-1088.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.