| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 4, December 2025, pages 182-191

Prognostic Value of Stroke Severity Measured by National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale Score for Post-Stroke Neuropsychiatric Outcomes in a Hispanic Population

Maria de los Angeles Alvareza, b, Xavier Andres Grandesa, Lina Karitza Zambranoa, Ana Sofia Cantosa

aDepartment of Research, Catholic University of Santiago of Guayaquil, Guayas, Guayaquil, Ecuador

bCorresponding Author: Maria de los Angeles Alvarez, Department of Research, Catholic University of Santiago of Guayaquil, Guayas, Guayaquil, Ecuador

Manuscript submitted October 1, 2025, accepted November 19, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: NIHSS Score: Post-Stroke Neuropsychiatric Outcomes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr1054

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Stroke is a leading cause of disability and mortality. Neuropsychiatric complications are frequent, and stroke severity measured by National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) may help identify patients at risk for adverse neuropsychiatric outcomes. The objective was to analyze whether stroke severity measured by the NIHSS score is associated with the development of neuropsychiatric complications after stroke in a Hispanic population.

Methods: This observational, analytical, retrospective study included 170 adults with CT-confirmed stroke treated in 2024 at a tertiary hospital in Guayaquil. Stroke severity (NIHSS), clinical variables, and neuropsychiatric outcomes were analyzed using chi-square tests, Mann-Whitney U, and multivariable logistic regression, adhering to STROBE and ethical standards (SPSS version 27.0). Results were expressed as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), considering P < 0.05 and including only models with an events-per-variable (EPV) ratio ≥ 6.

Results: A total of 170 adults (mean age 61.32 ± 14.62 years) were studied; 63.5% were male. Ischemic strokes comprised 56.5% and hemorrhagic 43.5%. Median NIHSS at admission was 7 (interquartile range (IQR) 4 - 13); categories: no deficit 6.5%, mild 25.9%, moderate 48.8%, moderate-severe 8.2%, severe 10.6%. Overall, 42.4% (n = 72) developed neuropsychiatric manifestation: cognitive impairment and sleep disturbances each occurred in 22.4%, behavioral disorders in 20.0%, depression in 15.30%, anxiety in 8.20%, and psychosis in 4.70%. Chi-square testing showed significant associations for moderate strokes with sleep disturbances (63.2%, P = 0.024), cognitive impairment (68.4%, P = 0.029), and behavioral disorders (76.5%, P = 0.003). Mann-Whitney comparisons indicated higher median NIHSS in patients with depression (12 vs. 7, P = 0.014), sleep disturbances (8 vs. 6, P = 0.025), and behavioral disorders (12 vs. 6, P = 0.002). Multivariable logistic regression revealed that younger age (Exp(B) = 0.957, P = 0.046), female sex (Exp(B) = 9.801, P < 0.001), and higher NIHSS scores (Exp(B) = 1.101, P = 0.010) independently predicted depression. Higher NIHSS scores also predicted sleep disturbances (Exp(B) = 1.072, P = 0.047) and behavioral disorders (Exp(B) = 1.071, P = 0.036), with female sex acting as a protective factor for behavioral disorders (Exp(B) = 0.227, P = 0.012). Cognitive impairment was associated with shorter time to onset (Exp(B) = 0.997, P = 0.037).

Conclusion: The NIHSS scale proved to be a useful tool not only for measuring the initial severity of stroke, but also for identifying the risk of developing neuropsychiatric complications.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular disease; Stroke; Neuropsychiatric disorders; Psychiatric sequelae

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Stroke is defined as a sudden-onset focal neurological deficit resulting from total or partial occlusion or rupture of a cerebral vessel, confirmed by neuroimaging or pathological findings. It remains the second leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide, primarily due to irreversible neuronal injury and functional impairment [1, 2]. In 2021, approximately 7.8 million new stroke cases were reported globally, with a slightly higher incidence in men (4.02 million) than in women (3.78 million), accounting for more than 3.5 million deaths [3]. The burden is disproportionately higher in developing countries, where modifiable vascular risk factors are more prevalent and epidemiological data are limited.

Strokes comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders with distinct pathophysiological mechanisms that determine lesion distribution, neurological severity, and prognosis. Ischemic stroke represents nearly 80% of all cases and results from vascular occlusion leading to decreased cerebral blood flow. The consequent ischemic cascade involves ATP depletion, ionic imbalance, glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation, ultimately causing neuronal death [4]. In contrast, hemorrhagic stroke, accounting for roughly 20% of cases, involves intracerebral or subarachnoid bleeding, producing both primary tissue compression and secondary injury mediated by inflammation, oxidative damage, and coagulation activation [5].

From a clinical perspective, accurate etiological classification is essential since each stroke subtype exhibits different risk factors, pathophysiology, and outcomes. The TOAST system distinguishes five major ischemic subtypes: large-artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism, small-vessel occlusion (lacunar), stroke of other determined etiology, and cryptogenic stroke. This classification is critical for estimating functional prognosis and guiding therapeutic decisions. In contrast, hemorrhagic stroke, depending on the location, is classified as intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage [6].

Beyond the neurological deficits, stroke frequently leads to neuropsychiatric sequelae, which arise from the interaction between structural brain injury, neurochemical alterations, and the psychological impact of the event [7, 8]. Post-stroke depression (PSD) is the most common complication, with reported prevalence ranging from 15% to 70%, typically associated with lesions involving the left frontal and subcortical regions, including the basal ganglia and limbic system [9, 10]. Secondly, anxiety can occur in 15-40% of cases and manifests as excessive and persistent worry, associated with lesions in the left cerebral hemisphere [10].

Cognitive impairment after stroke involves persistent disturbances in attention, executive function, and memory, often coexisting with affective symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and agitation [10, 11]. Behavioral disturbances, including irritability and emotional lability, occur in about one-third of patients and are linked to orbitofrontal and limbic involvement. Less frequently, post-stroke psychosis (1-2% of cases) manifests with delusions or hallucinations, and has been associated with right temporo-parietal and frontoparietal lesions [11, 12].

Additionally, sleep-related breathing disorders, particularly obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), have emerged as both a risk factor for incident stroke and a complication during recovery. The intermittent hypoxemia, sympathetic overactivation, and hemodynamic instability characteristic of OSA contribute to cerebral ischemia and poor functional outcomes. Its presence increases recurrence risk and long-term mortality, underscoring the need for early recognition and management [13].

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is the most widely used tool for quantifying neurological deficit severity in acute stroke. Higher NIHSS scores reflect greater impairment of motor, sensory, and cognitive domains and are associated with poorer functional recovery [14, 15]. Previous studies have reported that higher NIHSS scores during the acute phase correlate with subsequent depressive symptoms, particularly in patients with basal ganglia lesions [16]. This relationship may be mediated by neurohumoral activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic-adrenal systems, linking stroke severity with long-term cognitive and emotional outcomes [17, 18].

Likewise, a lower NIHSS score is associated with better cognitive recovery and a lower prevalence of emotional disturbances, such as apathy and emotional instability. The findings suggest that the scale is useful for predicting functional recovery and cognitive and emotional outcomes [19]. Incorporating the NIHSS scale into the comprehensive assessment of stroke patients allows for early detection of the risk of developing disorders such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment.

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to analyze whether stroke severity measured by the NIHSS score is associated with the development of neuropsychiatric complications after stroke in a Hispanic population. We hypothesize that higher NIHSS scores are independently associated with a greater risk of developing depression, cognitive impairment, sleep disorders, and behavioral changes during clinical follow-up.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

An observational, analytical, retrospective study was conducted based on a review of medical records from 170 adult patients diagnosed with cerebrovascular events and treated between January and December 2024 at a tertiary care hospital in Guayaquil, Ecuador. The Ethics Committee of Hospital Abel Gilbert Ponton evaluated and authorized this study protocol under approval code HAGP-UDI-2024-069-O. The study adhered to international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The manuscript was structured according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to ensure transparency, completeness, and methodological rigor.

Patient selection

Eligible participants were adults (age 25 - 89 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovascular event on computed tomography (CT) who were treated consecutively at a tertiary care hospital in Guayaquil between January 1, and December 31, 2024. A screening log was kept of 650 clinical histories screened, 480 were excluded for predefined reasons (incomplete records n = 327; prior neuropsychiatric disorder n = 42; brain tumor n = 111), yielding 170 patients for analysis. Each patient contributed a single record, and in cases of multiple admissions the index admission for the cerebrovascular event was used. Minimum clinical follow-up to ascertain neuropsychiatric outcomes was 7 days (median follow-up: 120 days).

Definition and assessment of neuropsychiatric outcomes

Neuropsychiatric outcomes comprised cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, behavioral changes, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and psychotic symptoms. Outcomes were recorded if documented by a psychiatrist in the medical record during hospitalization or outpatient follow-up, based on routine clinical assessment and, when explicitly stated, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria. Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized form, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Comorbidities and stroke etiology were obtained from patients’ medical and laboratory records according to predefined definitions.

Data collection and variables

Variables were grouped into three categories: sociodemographic (age, sex), clinical (comorbidities, type and etiology of cerebrovascular event, post-event neuropsychiatric manifestations, and time since the event), and neurological (NIHSS score at admission). Stroke severity was assessed using the NIHSS at admission and categorized into five levels: no deficit (0), mild (1 - 4), moderate (5 - 15), moderate to severe (16 - 20), and severe (21 - 42).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as median and interquartile range (IQR) when non-normal; categorical variables as counts and percentages. Bivariate associations between NIHSS severity categories and neuropsychiatric outcomes were evaluated with the chi-square test (Fisher’s exact test used when expected cell counts < 5). Comparisons of NIHSS distributions between groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. For each neuropsychiatric outcome with sufficient events, multivariable binary logistic regression models were fitted to estimate adjusted odds ratios (Exp(B)) and only when sufficient events were available (events-per-variable (EPV) ≥ 6).

Predictor variables (selected a priori) included age, sex, time from stroke onset to assessment (days), NIHSS score at admission (modeled as a continuous covariate), stroke type (ischemic vs hemorrhagic), and presence of ≥ 3 comorbidities (binary). EPV was calculated for each model; models with EPV < 6 were reported descriptively. Model assumptions were assessed as follows: independence of observations was ensured by including only the index admission for each patient; multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factor (VIF < 5 for all predictors). Model fit and calibration were assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and Nagelkerke R2.

| Results | ▴Top |

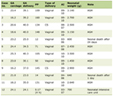

A total of 170 adult patients diagnosed with cerebrovascular events were included in this analysis. Participants were aged between 25 and 89 years (mean: 61.32 ± 14.62 years; median: 59.5 years). Male patients predominated, representing 63.52% of the cohort. Regarding the type of cerebrovascular event, 56.47% were ischemic and 43.53% were hemorrhagic (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population |

Among patients with hemorrhagic stroke, the most common cause was hypertension (59.5%; n = 44), followed by aneurysm (20.3%; n = 15), trauma (12.2%; n = 9), indeterminate cause (5.4%; n = 4), and arteriovenous malformation (2.7%; n = 2). In patients with ischemic stroke, the leading cause was cerebral arterial thrombosis (32.3%; n = 31), followed by atherosclerotic/stenotic disease (22.9%; n = 22), microangiopathy associated with hypertension (17.7%; n = 17), cardioembolic events (16.7%; n = 16), and indeterminate cause (10.4%; n = 10) (Table 1).

In terms of comorbidities, arterial hypertension was the most frequent (74.70%; n = 127), followed by diabetes mellitus (68.82%; n = 117), dyslipidemia (47.64%; n = 81), chronic kidney disease (45.88%; n = 78), alcohol abuse (23.5%; n = 40), smoking (20.6%; n = 35) and cardiac disease (12.35%; n = 21). To assess the severity of neurological impairment, the NIHSS scores at admission were analyzed. The median NIHSS score at admission was 7 (IQR: 4 - 13). Based on the NIHSS classification, 6.47% (n = 11) of patients had no deficit (score = 0), 25.88% (n = 44) were categorized as having mild stroke (1 - 4), 48.82% (n = 83) as moderate (5 - 15), 8.24% (n = 14) as moderate to severe (16 - 20), and 10.59% (n = 18) as severe (21 - 42) (Table 1).

During follow-up, 42.35% of patients (n = 72) presented neuropsychiatric manifestations. The most frequently documented symptoms were cognitive impairment and sleep disturbances (each observed in n = 38; 52.77% of symptomatic patients), followed by behavioral disorders (n = 34; 47.22%), depressive symptoms (n = 26; 36.11%), anxiety (n = 14; 19.44%), and psychotic symptoms (n = 8; 11.11%) (Table 1).

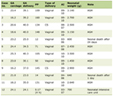

To explore the association between stroke severity and neuropsychiatric manifestations, a chi-square test was performed. Significant associations were observed mainly among patients with moderate strokes, of whom 63.2% had sleep disturbances (P = 0.024), 68.4% cognitive impairment (P = 0.029), and 76.5% behavioral disorders (P = 0.003). In contrast, no statistically significant associations were found between severity and the presence of depressive symptoms (P = 0.155), anxiety (P = 0.065), or psychotic symptoms (P = 0.577) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Relationship Between the Degrees of Severity of the Cerebrovascular Event Using the NIHSS Scale and Neuropsychiatric Manifestations |

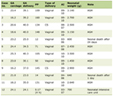

To determine whether stroke severity at admission was related to the later development of neuropsychiatric symptoms, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare NIHSS score distributions between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups. Patients who developed depression had a median NIHSS score of 12 (IQR: 6 - 18), which was significantly higher than in the group without depression (median = 7, IQR: 3.5 - 12; U = 2,437, Z = 2.451, P = 0.014) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Relationship Between the Severity of the Cerebrovascular Event Upon Admission and the Manifestation of Neuropsychiatric Disorders |

Similarly, patients with sleep disturbances had a median score of 8 (IQR: 5 - 15) compared to 6 (IQR: 3 - 11) in the control group (U = 3,104, Z = 2.234, P = 0.025), while those with behavioral disorders had a median of 12 (IQR: 7 - 16) versus 6 (IQR: 3 - 10) (U = 3,098, Z = 3.068, P = 0.002). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in NIHSS scores among patients with anxiety (U = 1,363, Z = 1.539, P = 0.124), psychotic disorders (U = 789, Z = 1.040, P = 0.299), or cognitive impairment (U = 2,978.5, Z = 1.575, P = 0.115) (Table 3). These results indicate that depression, sleep disturbances, and behavioral disorders are significantly more prevalent in patients with higher stroke severity.

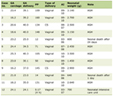

Binary logistic regression identified independent predictors of post-stroke neuropsychiatric manifestations. Adequate EPV (≥ 6) ratios were verified before model construction. Multivariate analyses were therefore conducted only for depression, cognitive impairment, behavioral disorders, and sleep disturbances, as the limited number of events for anxiety (n = 14) and psychotic symptoms (n = 8) precluded reliable modeling.

Specifically, the depression model showed good fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 9.81, df = 7, P = 0.199) and explained 36.0% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.360). Models for cognitive impairment (χ2 = 10.39, P = 0.168, R2 = 0.194) and behavioral disorders (χ2 = 11.27, P = 0.127, R2 = 0.186) also demonstrated acceptable calibration. However, the model for sleep disturbances (χ2 = 20.19, P = 0.005, R2 = 0.196) displayed poor fit and limited predictive accuracy. All predictors included in the multivariate models had acceptable multicollinearity (VIF < 5).

For depression, younger age (Exp(B) = 0.957, P = 0.046), female sex (Exp(B) = 9.801, P < 0.001), and higher stroke severity at admission (NIHSS, Exp(B) = 1.101, P = 0.010) were significant predictors, indicating that depression was more frequent among women and patients with more severe strokes, while increasing age showed a protective effect (Table 4).

Click to view | Table 4. Association Between Clinical Variables and the Presence of Neuropsychiatric Manifestations in Patients With Cerebrovascular Events |

Regarding other outcomes, higher NIHSS scores were also associated with a greater likelihood of sleep disturbances (Exp(B) = 1.072, P = 0.047) and behavioral disorders (Exp(B) = 1.071, P = 0.036). Additionally, female sex showed a significant association with behavioral disorders (Exp(B) = 0.227, P = 0.012), suggesting a lower risk compared to men, whereas shorter time to onset was related to cognitive impairment (Exp(B) = 0.997, P = 0.037). The presence of ≥ 3 comorbidities did not independently predict any neuropsychiatric manifestation after adjustment for age, sex, stroke severity, and time to onset (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our research revealed a high frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms in individuals who have experienced a stroke, especially in those with a significantly high score on the NIHSS score. During medical follow-up, more than 42% of participants presented some form of emotional, behavioral, cognitive, or sleep disorder. This finding supports the growing evidence that neuropsychiatric complications are one of the most significant sequelae of stroke, with notable consequences on quality of life, functional prognosis, and the burden on the healthcare system [8].

A particularly relevant finding of the present study was the significant association between neurological severity, measured using the NIHSS scale, and the onset of depression after a stroke. As the NIHSS score increased, so did the likelihood of the patient developing depressive symptoms. This correlation is consistent with several studies that identify depression as the most common neuropsychiatric complication after a severe stroke. Recent research suggests that the rate of post-stroke depression varies between 18% and 33% in the first year, even in cases considered clinically mild or moderate [10, 20].

Dong et al [20] in their longitudinal study showed that in patients with ischemic stroke and/or intracranial hemorrhage classified as mild and moderate by NIHSS (NIHSS < 16), the prevalence of depression was around 35.3% at 3 months, 24.9% at 6 months, and remained stable at 25.7% at 12 months after stroke. In contrast, the presence of depressive symptoms in our study was highlighted in 36.11% of patients, with a frequency of 46.15% in patients with moderate NIHSS. This trend and dynamic depressive symptomatology suggest that depression after a cerebrovascular event tends to persist beyond 6 months in patients classified as mild and moderate severity.

Similarly, Yan et al [21] conducted a case-control study in 2025 determining the correlation between the NIHSS score and the risk of post-stroke depression. The findings of their study, involving a total of 172 patients with acute cerebral infarction, established that the baseline NIHSS score correlates positively with the 3-month risk of depression after an infarction (P < 0.05), and multivariate logistic regression reveals that sex (OR = 2.168, 95% CI 1.038 - 4.526), NIHSS (OR = 1.164, 95% CI 1.022 - 1.325), and neuron-specific enolase (OR = 1.180, 95% CI 1.037 - 1.343) were independent factors for this outcome. In contrast, in our study, multivariate analysis using logistic regression showed that female sex (P < 0.001, Exp(B) = 9.801) and NIHSS on admission (P = 0.011; Exp(B) = 1.101) were independent factors correlated with the onset of depressive symptoms.

It has been suggested that lesions in areas such as the frontal lobe, basal ganglia, and limbic system may alter the transmission of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and noradrenaline, reducing neuroplasticity and facilitating the onset of depressive symptoms. It has also been observed that systemic inflammation and the activation of proinflammatory cytokines may increase emotional vulnerability in these patients, highlighting the need for a multimodal approach that includes both neurobiological and psychosocial factors [22, 23]. Consequently, the observed relationship between NIHSS and neuropsychiatric outcomes may not be causal, but rather a result of collinearity of anatomical lesion burden, anatomical location, and functional disability.

Another significant finding of this study was the detection of sleep disorders, which were statistically associated with stroke severity. It is estimated that between 30% and 70% of patients who have suffered a stroke experience some type of sleep disorder, with insomnia, sleep apnea, and circadian rhythm disturbances being the most prominent [24-26]. Sleep disturbances not only cause discomfort, but also negatively affect neuro-recovery. Research has shown that patients who experience sleep disorders after a stroke have a less favorable neurological prognosis, a higher probability of relapse, and progressive cognitive impairment [26, 27].

In their cross-sectional study, Kim et al [28] investigated the prevalence of sleep disorders and their influence on the prognosis after acute cerebral infarction using the NIHSS at 7 days (NIHSS-7) and the modified Rankin scale at 3 months (mRS-3). Their results in a total of 241 patients showed that the NIHSS-7 scale is associated with the optimized sleep apnea scale for stroke (SOS) (standardized β = 0.281, P < 0.001) and mRS-3 with the Korean Insomnia Severity Index (ISI-K) (standardized β = 0.219, P = 0.001) and with SOS (standardized β = 0.171, P = 0.011) [28].

In contrast, our research revealed that patients with sleep disturbances had a median severity of 8 (IQR: 5 - 15), compared to 6 (IQR: 3 - 11) in the control group (U = 3,104, Z = 2.234, P = 0.025). The use of multivariate logistic regression showed that the NIHSS at admission correlates with the onset of sleep disturbances (P = 0.047; Exp(B) = 1.072).

Behavioral disorders were identified as one of the most frequent changes in study participants, especially among those who suffered a moderate to severe stroke. Irritability, difficulty concentrating, emotional instability, and agitation are common manifestations resulting from lesions in the frontal, orbitofrontal, and limbic structures. These areas are directly linked to behavior control and decision-making [8, 29]. Such alterations can significantly complicate the rehabilitation process, generate conflicts in interpersonal relationships, and increase the burden on caregivers, so it is vital to identify them early in order to implement behavioral and psychosocial management strategies.

Sensenbrenner et al [30] evaluated the frequency of social cognition disorders 3 years after a first ischemic stroke event and, in their population of 43 patients with an NIHSS of 0 ± 1 (interquartile range), 21 patients (46.5%) had poor results in the facial emotion subtest, a factor associated with low educational attainment (P < 0.001). Fourteen (34.2%) scored low on the faux-pas recognition subtest, a factor associated with episodic memory disorders (P < 0.01). These results point to the high frequency of social cognitive impairment after a first ischemic event in young patients.

Our research revealed similar results in terms of frequency; approximately 47.22% of patients presented behavioral disorders. The Mann-Whitney U test in those with behavioral disorders showed a median of 12 (IQR: 7 - 16) compared to 6 (IQR: 3 - 10) in the control group (U = 3,098, Z = 3.068, P = 0.002). Likewise, multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrates a statistically significant correlation between the NIHSS score at admission and behavioral disorders (P = 0.036; Exp(B) = 1.071).

As for post-stroke anxiety, although its frequency was lower compared to other symptoms, its clinical relevance should not be ignored. Although in this study the relationship with stroke severity was not statistically significant, previous studies have shown that up to 25-30% of patients may experience symptoms of anxiety during the acute or subacute phase of stroke [31, 32]. Anxiety after a stroke is more associated with personal factors such as age, psychiatric history, stressful life experiences, or lack of social support, rather than the location or severity of the brain injury.

These findings were demonstrated by Zhang et al [33] in their retrospective study using multivariate analysis with logistic regression, which elucidated the factors influencing the development of anxiety. Among these, educational level, underlying diseases, income, and rural residence were statistically associated with its onset (P < 0.05). This lack of connection with neurological severity supports the idea that its origin could be more related to psychological reactions than to direct structural damage.

In a cross-sectional study conducted by Ahmed et al [34] during the COVID-19 pandemic, which included 50 participants, post-stroke depression was evident in 36% of patients and post-stroke anxiety in 32%; multivariate analysis with logistic regression showed that the NIHSS (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 0.74 - 3.37; P = 0.01) is significantly associated with the development of post-stroke depression. However, post-stroke anxiety was related to thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level (OR: 8.32, 95% CI: 1.42 - 47.23; P = 0.02) and discontinuation of rehabilitation (β: -0.96, 95% CI: 1.90 - 0.02; P = 0.04). In contrast, in our study, no significant association was found between NIHSS score and the development of anxiety (P = 0.124), which aligns with previous evidence suggesting that post-stroke anxiety may be more influenced by psychosocial rather than neurological factors.

An interesting finding was the lack of significant correlation between cognitive impairment and stroke severity, which may seem paradoxical. However, this perspective is consistent with research suggesting that post-stroke cognitive impairment depends more on the anatomical location of the damage than on the amount of tissue affected [35, 36]. Furthermore, the existence of previous brain damage or limited cognitive reserve prior to the event may have a crucial influence on the onset and progression of cognitive impairment, especially in older people or those with concomitant vascular diseases.

Long-term studies have shown that cognitive impairment can persist or even worsen at 3, 6, and 12 months after stroke, regardless of the initial NIHSS score. Li et al [37], in a retrospective case-control study, analyzed the risk factors and characteristics of cognitive impairment in 183 patients with ischemic cerebral infarction. A multiple logistic regression analysis was used, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between the cognitive impairment group and the normal cognition group, highlighting age ≥ 65, presence of stroke, atherosclerotic plaques in carotid arteries, NIHSS score ≥ 5, anterior circulation infarction, and presence of multiple infarction lesions as risk factors for cognitive impairment.

Similarly, Koton et al [38] demonstrated that the risk of developing dementia increased with the number and severity of strokes. The hazard ratio (HR) adjusted risk of dementia was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.49 - 2.00) in asymptomatic to mild stroke, 3.47 (95% CI, 2.23 - 5.40) for moderate to severe stroke, 3.48 (95% CI, 2.54 - 4.76) for two or more minor to mild strokes, and 6.68 (95% CI, 3.77 - 11.83) for two or more moderate to severe strokes. In our research, the time of onset of the cerebrovascular event showed a significant inverse relationship only with cognitive impairment (P = 0.037; Exp(B) = 0.997). The NIHSS score, age, and female sex did not reveal statistically significant results (P > 0.05) in terms of the risk of cognitive impairment.

Finally, psychotic symptoms were rare in the study group, which is consistent with the literature, which reports a prevalence of 1-3% in the post-stroke phase [8]. Hallucinations and delusions are often related to lesions in the right hemisphere, especially in the temporoparietal areas, and tend to be more common in patients with a history of psychiatric disorders, previous cognitive impairment, or advanced age [8, 39].

Although the prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders in patients with cerebrovascular disease is relatively high, there are a limited number of case reports describing psychotic symptoms following the development of a cerebral ischemic event [40]. In general, the onset of this condition has been reported a few days after the vascular event and tends to disappear in the following days [41]. In our research, multivariate analysis did not determine statistically significant associations for the development of psychotic disorders in the population.

Strength and limitations

This study presents several methodological strengths that reinforce the reliability of its findings. The analysis was based on a well-defined cohort of consecutively treated patients with cerebrovascular events confirmed by neuroimaging, minimizing selection inconsistencies. The strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, the standardized extraction of data by independent reviewers, and the adherence to STROBE guidelines ensured methodological transparency and internal consistency. Furthermore, the application of robust statistical procedures, including the verification of EPV ratios, multicollinearity diagnostics, and model calibration tests, enhances the credibility of the multivariate analyses.

However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective nature of the study relies on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which may limit the uniformity of neuropsychiatric assessments. The follow-up duration was heterogeneous among participants, which could have influenced the timing of symptom detection. Neuropsychiatric outcomes were identified from clinical documentation and, when explicitly stated, based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. However, the absence of standardized psychometric assessments may have led to underrecognition of mild or subclinical manifestations. Finally, as a single-center study conducted in a tertiary care setting, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other healthcare contexts or community populations. Despite these constraints, the study provides a solid, methodologically consistent contribution to understanding the link between neurological severity and neuropsychiatric sequelae following stroke.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the prognostic relevance of early clinical indicators, particularly neurological severity, in anticipating post-stroke neuropsychiatric outcomes. Integrating systematic neuropsychiatric evaluation into the acute management of stroke may enable the early identification of patients at higher risk for depression, behavioral disorders, and cognitive impairment. Establishing standardized detection protocols and timely multidisciplinary interventions could enhance long-term recovery, improve quality of life, and reduce the overall burden of post-stroke disability in Hispanic populations.

Future studies should use a potential, multicenter study design and neuroimaging biomarkers to analyze the causal pathways between brain lesion burden, location, and neuropsychiatric sequelae. Studies should compare lacunar strokes and non-lacunar strokes because of differences in pathophysiology, prognosis, and neuropsychiatric profile. Data show that lacunar infarctions because of small penetrating arteries in deep brain regions have different cognitive and emotional effects from non-lacunar stroke [37]. Differentiating the subtypes of stroke may help guide rehabilitation and secondary prevention. Other factors such as inflammatory markers, neuroendocrine response to stress, and genetic factors may stratify risk for post-stroke psychiatric sequelae.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare. No individuals or organizations outside the author group contributed to the research or manuscript.

Financial Disclosure

This study did not receive any specific grant or financial support from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies. The authors declare that there were no sponsors or funders involved in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Due to the retrospective nature of the research and absence of direct patient interaction, obtaining written informed consent was waived.

Author Contributions

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Maria de los Angeles Alvarez. Drafting of the manuscript: Maria de los Angeles Alvarez, Lina Karitza Zambrano, Ana Sofia Cantos, and Xavier Andres Grandes. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Maria de los Angeles Alvarez, Lina Karitza Zambrano, Ana Sofia Cantos, and Xavier Andres Grandes. Concept and design: Maria de los Angeles Alvarez and Lina Karitza Zambrano.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Berrios W, Deschle F, Marroquin V, Ziegler G, Farina S, Pacha MS, Cervino CV, et al. [Prospective study of neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms post-stroke]. Vertex. 2025;35(166):13-19.

doi pubmed - Arias Rodriguez FD, Ayala Pavon ME, Paredes Chamorro JD, et al. Enfermedad cerebro vascular isquemica diagnostico y tratamiento. TEJOM. 2023;6(1):28-41.

doi - Hou S, Zhang Y, Xia Y, Liu Y, Deng X, Wang W, Wang Y, et al. Global, regional, and national epidemiology of ischemic stroke from 1990 to 2021. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31(12):e16481.

doi pubmed - Gasull T, Arboix A. Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology of acute stroke: emphasis on biomarkers in the different stroke subtypes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9476.

doi pubmed - Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):720-731.

doi pubmed - Rathburn CM, Mun KT, Sharma LK, Saver JL. TOAST stroke subtype classification in clinical practice: implications for the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke nationwide registry. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1375547.

doi pubmed - Nemani K, Gurin L. Neuropsychiatric complications after stroke. Semin Neurol. 2021;41(1):85-100.

doi pubmed - Zhang S, Xu M, Liu ZJ, Feng J, Ma Y. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: Clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10(6):125-138.

doi pubmed - Xiao A, Wang R, Liu C, Wang X. Influencing factors and predictive models of early post-stroke depression in patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2025;25(1):104.

doi pubmed - Liu X, Cheng C, Liu Z, Fan W, Liu C, Liu Y. Longitudinal assessment of anxiety/depression rates and their related predictive factors in acute ischemic stroke patients: A 36-month follow-up study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(50):e28022.

doi pubmed - Ferro JM, Caeiro L, Figueira ML. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(5):269-280.

doi pubmed - Luna-Matos M, Mcgrath H, Gaviria M. Manifestaciones neuropsiquiatricas en accidentes cerebrovasculares. Rev Chil Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2007;45(2).

doi - Uscamaita K, Parra Ordaz O, Yazbeck Morell I, Pla MG, Sanchez-Lopez MJ, Arboix A. From molecular to clinical implications of sleep-related breathing disorders on the treatment and recovery of acute stroke: a scoping review. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025;47(3):138.

doi pubmed - Lyden P. Using the national institutes of health stroke scale: a cautionary tale. Stroke. 2017;48(2):513-519.

doi pubmed - Powers WJ. Acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):252-260.

doi pubmed - Klingbeil J, Brandt ML, Wawrzyniak M, Stockert A, Schneider HR, Baum P, Hoffmann KT, et al. Association of lesion location and depressive symptoms poststroke. Stroke. 2022;53(11):e467-e471.

doi pubmed - Zhanina MY, Druzhkova TA, Yakovlev AA, Vladimirova EE, Freiman SV, Eremina NN, Guekht AB, et al. Development of post-stroke cognitive and depressive disturbances: associations with neurohumoral indices. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44(12):6290-6305.

doi pubmed - Glymour MM, Berkman LF, Ertel KA, Fay ME, Glass TA, Furie KL. Lesion characteristics, NIH stroke scale, and functional recovery after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):725-733.

doi pubmed - Tsiakiri A, Plakias S, Vlotinou P, Terzoudi A, Serdari A, Tsiptsios D, Karakitsiou G, et al. Predictive markers of post-stroke cognitive recovery and depression in ischemic stroke patients: a 6-month longitudinal study. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2024;14(12):3056-3072.

doi pubmed - Dong L, Williams LS, Brown DL, Case E, Morgenstern LB, Lisabeth LD. Prevalence and course of depression during the first year after mild to moderate stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(13):e020494.

doi pubmed - Yan C, Zheng W, Si T, Huang L, Wen L, Shen H, Qu M. Nomogram combined neuron-specific enolase and NIHSS for prediction of post stroke depression. Int J Neurosci. 2025:1-8.

doi pubmed - Guo J, Wang J, Sun W, Liu X. The advances of post-stroke depression: 2021 update. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1236-1249.

doi pubmed - Krick S, Koob JL, Latarnik S, Volz LJ, Fink GR, Grefkes C, Rehme AK. Neuroanatomy of post-stroke depression: the association between symptom clusters and lesion location. Brain Commun. 2023;5(5):fcad275.

doi pubmed - Kojic B, Dostovic Z, Vidovic M, Ibrahimagic OC, Hodzic R, Iljazovic A. Sleep disorders in acute stroke. Mater Sociomed. 2022;34(1):14-24.

doi pubmed - Baylan S, Griffiths S, Grant N, Broomfield NM, Evans JJ, Gardani M. Incidence and prevalence of post-stroke insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;49:101222.

doi pubmed - Hasan F, Gordon C, Wu D, Huang HC, Yuliana LT, Susatia B, Marta OFD, et al. Dynamic prevalence of sleep disorders following stroke or transient ischemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2021;52(2):655-663.

doi pubmed - Zhang Y, Xia X, Zhang T, Zhang C, Liu R, Yang Y, Liu S, et al. Relationship between sleep disorders and the prognosis of neurological function after stroke. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1036980.

doi pubmed - Kim KT, Moon HJ, Yang JG, Sohn SI, Hong JH, Cho YW. The prevalence and clinical significance of sleep disorders in acute ischemic stroke patients-a questionnaire study. Sleep Breath. 2017;21(3):759-765.

doi pubmed - Markus HS. Emotions and behavior after stroke. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(3):243.

doi pubmed - Sensenbrenner B, Rouaud O, Graule-Petot A, Guillemin S, Piver A, Giroud M, Bejot Y, et al. High prevalence of social cognition disorders and mild cognitive impairment long term after stroke. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2020;34(1):72-78.

doi pubmed - Ayasrah S, Ahmad M, Basheti I, Abu-Snieneh HM, Al-Hamdan Z. Post-stroke anxiety among patients in jordan: a multihospital study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022;35(5):705-716.

doi pubmed - Todorov V, Dimitrova M, Todorova V, Mihaylova E. Assessment of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the early post-stroke period. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2020;62(4):695-702.

doi pubmed - Zhang T, Sun Y, Wang W, Wu Y. Incidence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression in individuals with acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2024;52(3):268-275.

doi pubmed - Ahmed ZM, Khalil MF, Kohail AM, Eldesouky IF, Elkady A, Shuaib A. The prevalence and predictors of post-stroke depression and anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(12):105315.

doi pubmed - El Husseini N, Katzan IL, Rost NS, Blake ML, Byun E, Pendlebury ST, Aparicio HJ, et al. Cognitive impairment after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023;54(6):e272-e291.

doi pubmed - Pinguet V, Duloquin G, Thibault T, Devilliers H, Comby PO, Crespy V, Ricolfi F, et al. Pre-existing brain damage and association between severity and prior cognitive impairment in ischemic stroke patients. J Neuroradiol. 2023;50(1):16-21.

doi pubmed - Li Y, Geng W, Zhang X, Mi B. Risk factors and characteristics analysis of cognitive impairment in patients with cerebral infarction during recovery period. Int J Neurosci. 2025;135(8):863-868.

doi pubmed - Koton S, Pike JR, Johansen M, Knopman DS, Lakshminarayan K, Mosley T, Patole S, et al. Association of ischemic stroke incidence, severity, and recurrence with dementia in the atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(3):271-280.

doi pubmed - Guo C, Stretz C, Anderson JR, El-Husseini N, Mac Grory B, Werner B, Yarnell S. Psychiatric sequelae of stroke affecting the non-dominant cerebral hemisphere. J Neurol Sci. 2021;430:120007.

doi pubmed - Barboza RB, De Freitas GR, Tovar-Moll F, Fontenelle LF. Delayed-onset post-stroke delusional disorder: a case report. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(3):287-291.

doi pubmed - Arboix A, Massons J, Garcia-Eroles L, Targa C, Comes E, Parra O, Oliveres M. Nineteen-year trends in risk factors, clinical characteristics and prognosis in lacunar infarcts. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35(3):231-236.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.