| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 4, December 2025, pages 199-202

Chronic Subdural Hematoma Presenting as Insidious Onset Unilateral Involuntary Movements

Michelle Cheriana, Ahmed Ba Theebb, c, Mehmood Rashidb

aUniversity of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA

bDepartment of Neurology, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA

cCorresponding Author: Ahmed Ba Theeb, Department of Neurology, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA

Manuscript submitted June 25, 2025, accepted September 17, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: cSDH with Unilateral Movement Symptoms

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr1039

| Abstract | ▴Top |

With the average age in Western countries continuing to rise, chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) has emerged as an increasingly common neurological condition in these countries. The condition is particularly prevalent among the elderly, with a markedly higher incidence in individuals over 65 years of age. We present the case of a 79-year-old female who developed left-sided choreiform movements or hemiballismus several days after a minor fall. Initial imaging revealed no acute findings; however, delayed magnetic resonance imaging revealed a small chronic right-sided subdural collection. Notably, the patient’s symptoms gradually improved over a 6-month period. Overall, this case illustrates that cSDH can present with delayed-onset hyperkinetic movements, likely through biochemical or microvascular effects on cortical function rather than solely mechanical pressure. It underscores the importance of considering cSDH in the differential diagnosis for delayed-onset movement disorders and highlights the value of follow-up imaging and clinical monitoring, even after seemingly minor trauma.

Keywords: Chronic subdural hematoma; Involuntary movements; Post-traumatic movement disorder

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Subdural hematoma (SDH) is a neurological condition characterized by the accumulation of blood in the subdural space. Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) commonly develops from a previously asymptomatic acute SDH, typically following minor or unnoticed trauma. The incidence correlates with age, ranging from approximately 3.4 per 100,000 in individuals under 65 of age to between 8 and 58 per 100,000 individuals over 65 years of age. The pathogenesis of cSDH involves hemorrhage into the subdural space, typically due to the tearing of bridging veins, followed by a cascade of inflammatory and angiogenic processes that contribute to hematoma expansion, especially in patients with cerebral atrophy or those undergoing chronic anticoagulant therapy [1].

Hemichorea and hemiballismus are hyperkinetic movement disorders most often caused by lesions in the contralateral striatum and subthalamic nucleus, respectively [2]. While common causes include stroke, neoplasm, and metabolic disturbances, post-traumatic hemichorea is rare and often overlooked, particularly when symptoms are delayed, and initial imaging appears normal [3]. This case illustrates a delayed-onset movement disorder following minor head trauma, where a small cSDH was found to be a likely contributing factor.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 79-year-old female presented with involuntary movements of the left upper and lower extremities, which began a few days to a week after she fell down a flight of stairs. She sustained notable bruising on the right side of her face but denied loss of consciousness or immediate neurological symptoms.

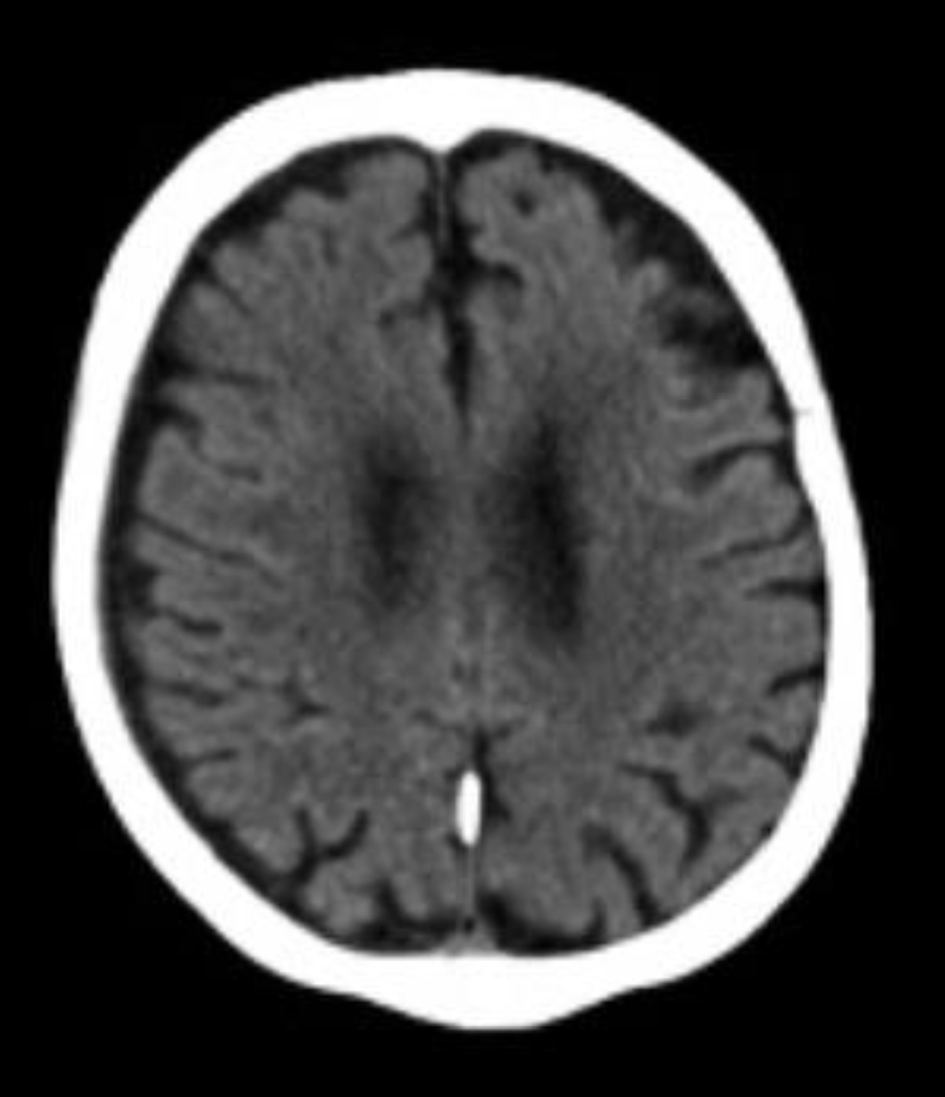

Initial computed tomography (CT) scans of the facial bones and cervical spine showed no acute abnormalities. The brain CT (Fig. 1) similarly revealed no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, or skull fracture.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Non-contrast head computed tomography obtained on June 9, 2024, a few days after sustaining the fall, demonstrates no acute intracranial abnormalities. |

Within a week of the fall, the patient noticed an insidious onset and gradually worsening involuntary swinging movements of the left arm and leg, occasionally affecting her ability to perform daily tasks. She also reported mild weakness in her left leg and balance issues.

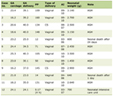

The neurological examination revealed that the patient was alert and oriented, with intact cranial nerves and language function. Mild weakness (4/5) was observed in the left hip flexion. Involuntary movements consistent with left hemiballismus and choreiform activity were observed in the left side of the face, arm, and leg. These movements could be temporarily suppressed but reappeared as she focused on performing examination maneuvers with her right side. Sensation and coordination were normal, except in the left arm, where the involuntary movements interfered. Gait evaluation revealed unsteadiness, antalgic movement, and frequent scissoring during tandem gait. Laboratory results, as shown in Table 1, were notable for low vitamin B12 and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels but were otherwise unremarkable.

Click to view | Table 1. Selected Laboratory Results on September 16, 2024 |

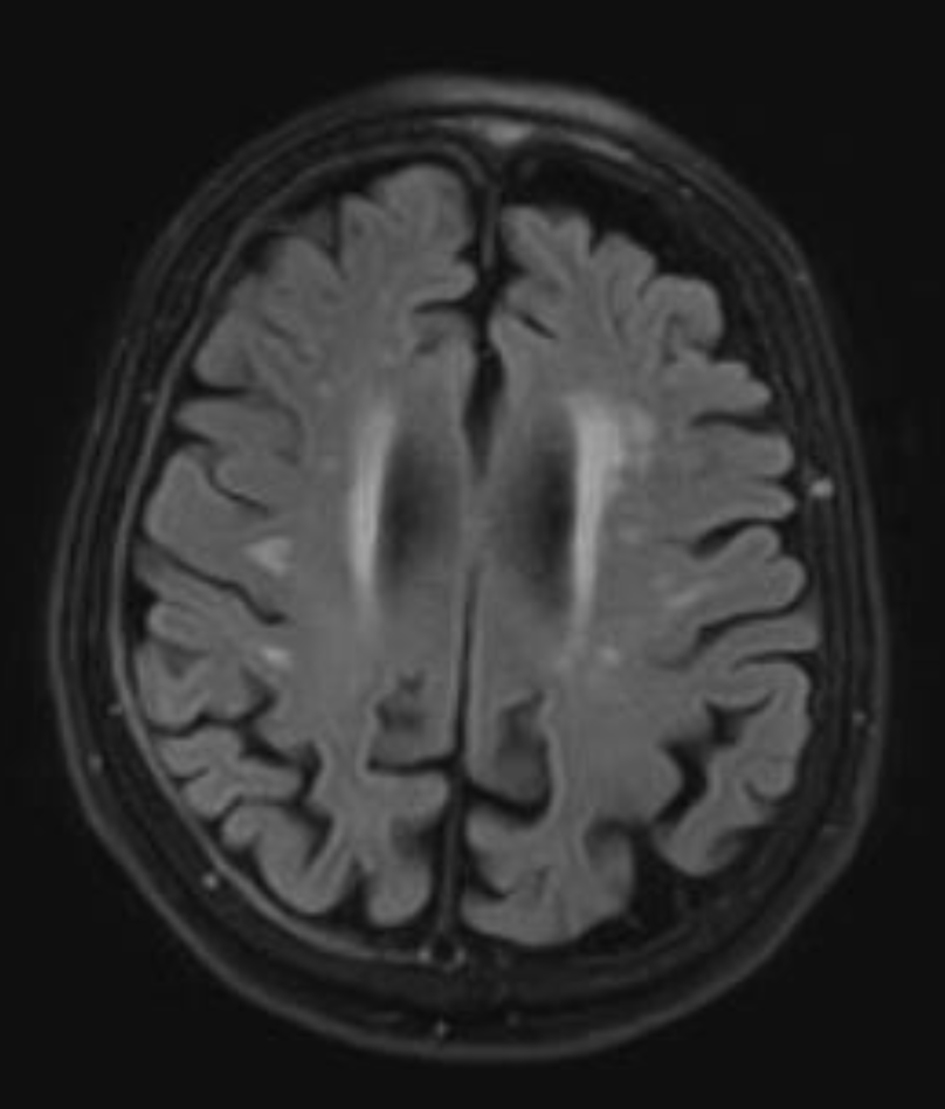

By the 4-month mark, her symptoms appeared stable to her, although her husband observed a continued mild progression. Around this time, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained, which revealed a small (2 mm) chronic right holohemispheric subdural collection with fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity, along with mild-to-moderate cerebral atrophy and chronic microvascular ischemic changes (Fig. 2). She was started on a low dose of topiramate, 25 mg twice daily, and used the medication for approximately 3 months before it was gradually tapered and discontinued. During this period, she also participated in supportive physical therapy for functional recovery.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging of the brain performed on October 10, 2024, reveals a small (2 mm), chronic-appearing, mildly enhancing right holohemispheric subdural collection. In addition, mild-to-moderate cerebral atrophy and chronic microvascular ischemic changes are present. |

At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that her symptoms had improved. Involuntary movements were infrequent, less disruptive, and milder in intensity. Her balance also improved, and her gait became more stable. A repeat non-contrast CT of the brain at 6 months showed no new intracranial abnormalities and stable chronic subdural fluid collection without an increase in size.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case highlights an uncommon presentation of delayed-onset hemichorea following minor head trauma. The absence of acute findings on initial imaging delayed diagnosis, but MRI later revealed a small chronic right-sided subdural collection and chronic microvascular ischemic burden (Figs. 1 and 2).

Hyperkinetic syndromes, characterized by symptoms like chorea, athetosis, and ballism, have traditionally been attributed to lesions affecting the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical circuits [4]. One theory suggests that chorea can arise from brain compression caused by a cSDH. This compression is thought to distort subcortical structures like the caudate nucleus. This distortion can lead to dysfunction of GABAergic neurons, reducing their inhibitory signals to the globus pallidus externa (GPe), resulting in its disinhibition. Subsequently, this disinhibition affects the globus pallidus interna (GPi) and substantia nigra reticularis (SNr), ultimately increasing thalamic output and boosting motor activity in the cortex and spine, leading to hyperkinetic movements. Small shifts in intracranial pressure could also temporarily affect deep gray matter pathways, which may help explain why movement symptoms like chorea or hemiballismus sometimes appear out of proportion to the actual size of the hematoma [5-8].

The cSDH in our case was small (2 mm) and did not appear to exert a significant mass effect. This raises the possibility that cortical dysfunction may independently contribute to the pathogenesis of hyperkinetic movement disorders through several proposed theories.

Significant evidence exists for a primary role of cortical structures in generating these movements, as reviewed by Li et al in the setting of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD). Interestingly, cSDH patients have been found to have a high resting motor threshold and less pronounced intracortical inhibition, factors that are also observed in PKD, suggesting a possible shared mechanism [9, 10].

Another proposed mechanism is reduced cerebral blood flow caused by the hematoma, which may affect the putamen and thalamus and can occur even in patients with minimal or no brain shift [8]. Additionally, local inflammatory responses surrounding the subdural collection could lead to neuronal dysfunction. This is likely facilitated by pro-inflammatory cytokines or blood breakdown products, such as iron, which can spread into nearby cortical and subcortical areas, interfering with neurotransmitter activity. Subtle shifts in blood flow and glymphatic clearance may also increase cortical excitability. In older patients, existing microvascular changes may further weaken basal ganglia circuits, making them more susceptible to even mild stress from a hematoma [11-14].

It is also important to consider that the direct head trauma itself may have contributed to the development of symptoms, while the hematoma could be an incidental finding. However, data regarding post-traumatic secondary movement disorders (SMDs) are limited. A prospective study of 103 patients found secondary chorea to be infrequent (2.9%) and not observed after trauma, even though trauma was implicated in 14.6% of SMDs [15]. In the literature, post-traumatic tremor and dystonia are more commonly described, while post-traumatic chorea is only rarely reported. In our case, the patient’s symptoms had an insidious onset, coinciding with the development of the cSDH. This suggests that hematoma played a primary role in the movement disorder’s onset, a finding similarly described in the literature.

While the patient was trialed on low-dose topiramate and participated in physical therapy, the lack of symptom recurrence after discontinuing the medication suggests that the improvement was more likely attributable to the natural course of recovery as the hematoma stabilized and underwent resorption.

Conclusion

This case highlights that delayed-onset hyperkinetic movement disorders can be a rare, yet important, clinical presentation of a cSDH, even in the absence of significant mass effect. The patient’s insidious symptom onset after minor trauma, coupled with the eventual spontaneous improvement, suggests that the cSDH was a contributing factor, possibly through biochemical and microvascular mechanisms rather than solely mechanical pressure. This case underscores the importance of considering SDH in the differential diagnosis for patients with delayed movement disorders, and it emphasizes the value of repeat imaging and longitudinal follow-up for accurate diagnosis and management. Further research is needed to better understand the correlation between small cSDH and delayed-onset movement disorders and to elucidate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The study was supported by Department of Neurology, University of Toledo.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Michelle Cherian contributed to the collection and organization of clinical data, literature review, and drafting the initial manuscript. Mehmood Rashid, MD provided senior supervision, critical revision of the manuscript, and expert input in the neurological evaluation and case interpretation. Ahmed Ba Theeb, MD contributed to interpretation of findings, literature synthesis, and final editing and approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Ducruet AF, Grobelny BT, Zacharia BE, Hickman ZL, DeRosa PL, Andersen KN, Sussman E, et al. The surgical management of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35(2):155-169; discussion 169.

doi pubmed - Ilic A, Semnic M, Stefanovic D, Galic V, Zivanovic Z. Chorea Hyperglycemia Basal Ganglia Syndrome-A Rare Case of Bilateral Chorea-Ballismus in Acute Non-Ketotic Hyperglycemia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2021;24(5):824-826.

doi pubmed - Cardoso F, Seppi K, Mair KJ, Wenning GK, Poewe W. Seminar on choreas. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(7):589-602.

doi pubmed - Fukumura M, Murase S, Kuroda Y, Nakazawa K, Gon Y. Secondary parkinsonism caused by chronic subdural hematomas owing to compressed cortex and a disturbed cortico-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;1(24):CASE21216.

doi pubmed - Hwang KJ, Hong IK, Ahn TB, Yi SH, Lee D, Kim DY. Cortical hemichorea-hemiballism. J Neurol. 2013;260(12):2986-2992.

doi pubmed - Carbayo A, Sarto J, Santana D, Compta Y, Urra X. Hemichorea as presentation of acute cortical ischemic stroke. Case series and review of the literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(10):105150.

doi pubmed - Tanaka A, Nakayama Y, Yoshinaga S. Cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure in chronic subdural hematomas. Surg Neurol. 1997;47(4):346-351.

doi pubmed - Ralot TK, Chahar C, Sharma JK, Hegde CV, GR. Acute hemichorea associated with ipsilateral chronic subdural hematoma. Int J Res Med Sci. 2021;9(1):287-289.

- Li ZY, Tian WT, Huang XJ, Cao L. The pathogenesis of paroxysmal Kinesigenic dyskinesia: current concepts. Mov Disord. 2023;38(4):537-544.

doi pubmed - Kawasaki Y, Fujiki M, Ooba H, Sugita K, Hikawa T, Abe T, Ishii K, et al. Short latency afferent inhibition associated with cortical compression and memory impairment in patients with chronic subdural hematoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(7):976-980.

doi pubmed - Edlmann E, Giorgi-Coll S, Whitfield PC, Carpenter KLH, Hutchinson PJ. Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):108.

doi pubmed - Holl DC, Volovici V, Dirven CMF, Peul WC, van Kooten F, Jellema K, van der Gaag NA, et al. Pathophysiology and nonsurgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: from past to present to future. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:402-411.e402.

doi pubmed - Kim HC, Ko JH, Yoo DS, Lee SK. Spontaneous resolution of chronic subdural hematoma : close observation as a treatment strategy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59(6):628-636.

doi pubmed - Ivamoto HS, Lemos HP, Jr., Atallah AN. Surgical treatments for chronic subdural hematomas: a comprehensive systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:399-418.

doi pubmed - Netravathi M, Pal PK, Indira Devi B. A clinical profile of 103 patients with secondary movement disorders: correlation of etiology with phenomenology. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(2):226-233.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.