| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 4, December 2025, pages 211-217

Delayed Development of an Occult Pseudoaneurysm After Coiling of a Ruptured Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysm

Mostafa Mahmouda, b , Muhammad Mohsin Khana

, Ehab Mahmouda

, Osman Koca

, Sirajeddin Belkhaira

aHamad Medical Corporation, Neuroscience Institute, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

bCorresponding Author: Mostafa Mahmoud, Hamad Medical Corporation, Neuroscience Institute, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

Manuscript submitted September 22, 2025, accepted December 6, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: Delayed ACoA Pseudoaneurysm After Coiling

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr1052

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Aneurysm disappearance and reappearance is a rare condition, typically described in isolated case reports. We present a case of rebleeding following coiling of a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of rebleeding due to the development of a pseudoaneurysm arising on the opposite wall of a coiled anterior communicating aneurysm, in which microsurgical clipping, coiling and flow diversion were all applied. The pseudoaneurysm demonstrated recanalization 1 week after surgical clipping, necessitating endovascular coiling. Subsequently, a flow diverter was deployed 8 days after coiling, following early recanalization at the pseudoaneurysm base. At 10 months, the follow-up angiography confirmed complete exclusion of both the pseudoaneurysm and the opposite wall aneurysm. This case illustrates the aggressive course of cerebral pseudoaneurysms, drawing the attention to the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges they present.

Keywords: Subarachnoid hemorrhage; Pseudoaneurysm; ACoA

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Disappearance and reappearance of cerebral aneurysms have been reported both in the acute phase of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and in unruptured cases, most often case reports.

We treated a patient who presented with SAH due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysm located on its anteroinferior wall using an uneventful coiling technique. Initial two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) angiography showed no blister or pseudoaneurysm on the posterosuperior wall. Ten days later, the patient experienced rebleeding, and emergent angiography revealed a newly formed pseudoaneurysm on the opposite wall of the previously coiled aneurysm.

This report highlights the diagnostic and management challenges raised by rebleeding in cases with no angiographic evidence of recanalization or morphological changes in a recently treated aneurysm following acute SAH. It underscores the aggressive behavior of pseudoaneurysms which require early diagnosis and prompt management.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 38-year-old gentleman presented with sudden severe headache and neck stiffness. He was slightly drowsy but responsive to commands and oriented with an estimated Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 14. Blood pressure (BP) was 172/107 mm Hg; other vital signs were within the normal range. Hydralazine (10 mg) was administered, reducing the BP to 155/97 mm Hg.

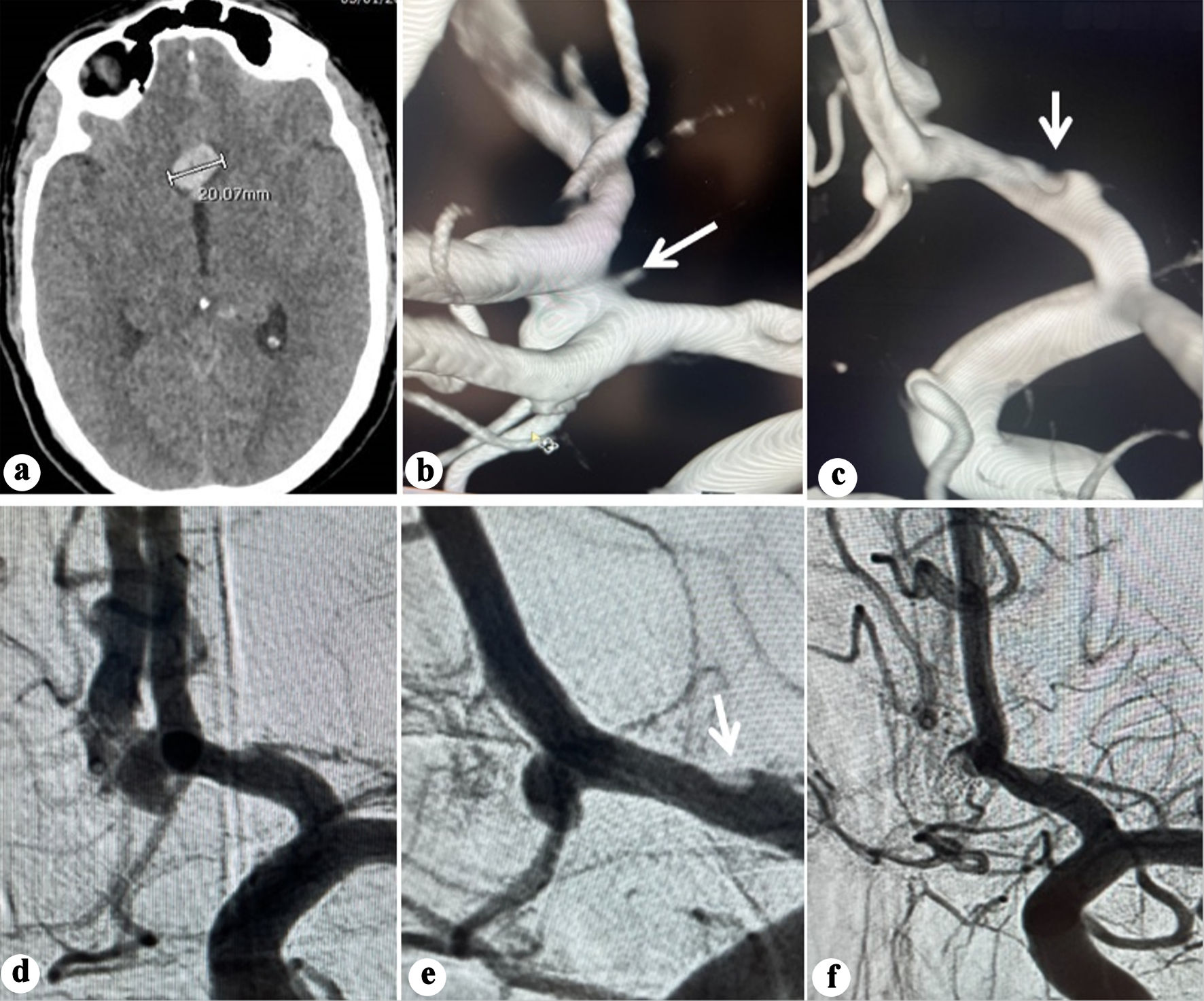

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography (CTA) revealed diffuse SAH with an interhemispheric hematoma measuring 20 mm in maximum dimension (Fig. 1a), caused by an anterior communicating aneurysm.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Plain CT showing interhemispheric blood and hematoma (20.07 mm). (b) Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction angiography showing an anterior communicating aneurysm arising from the anteroinferior wall. Note the irregularity observed in A1 segment (arrow). (c) 3D reconstruction angiography showing no abnormality on the posterosuperior wall of the ACoA (arrow). (d) Anteroposterior view angiography showing the ACoA aneurysm. (e) Oblique working projection pre-coiling of the ACoA aneurysm. Note the irregularity observed in A1 segment (arrow). (f) Oblique projection angiography post coiling of the ACoA aneurysm. ACoA: anterior communicating artery; CT: computed tomography. |

He underwent endovascular coiling 2 h after admission. A Benchmark 071 guiding catheter (Penumbra, Alameda, CA, USA) was positioned in the cervical internal carotid artery (ICA). 2D and rotational angiography with 3D reconstruction confirmed an ACoA aneurysm arising from the anteroinferior wall (Fig. 1b-e) while no abnormality on the posterosuperior wall was detected. An irregularity at the A1 segment evident on both 2D and 3D angiography was of particular concern and was interpreted as a possible indicative of arterial wall dysplasia (Fig. 1b, e).

A Hyperglide balloon 4 × 10 mm, (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was positioned from the left A1 to left A2. Three Target coils (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA; total length 15 cm) were deployed, leaving a neck remnant (Raymond-Roy grade 2) (Fig. 1f). The procedure was uneventful and completed within 40 min, with intraoperative BP maintained between 100/58 and 119/62 mm Hg. The patient awoke with no alteration in his neurological status and progressively improved to GCS 15 by the next day.

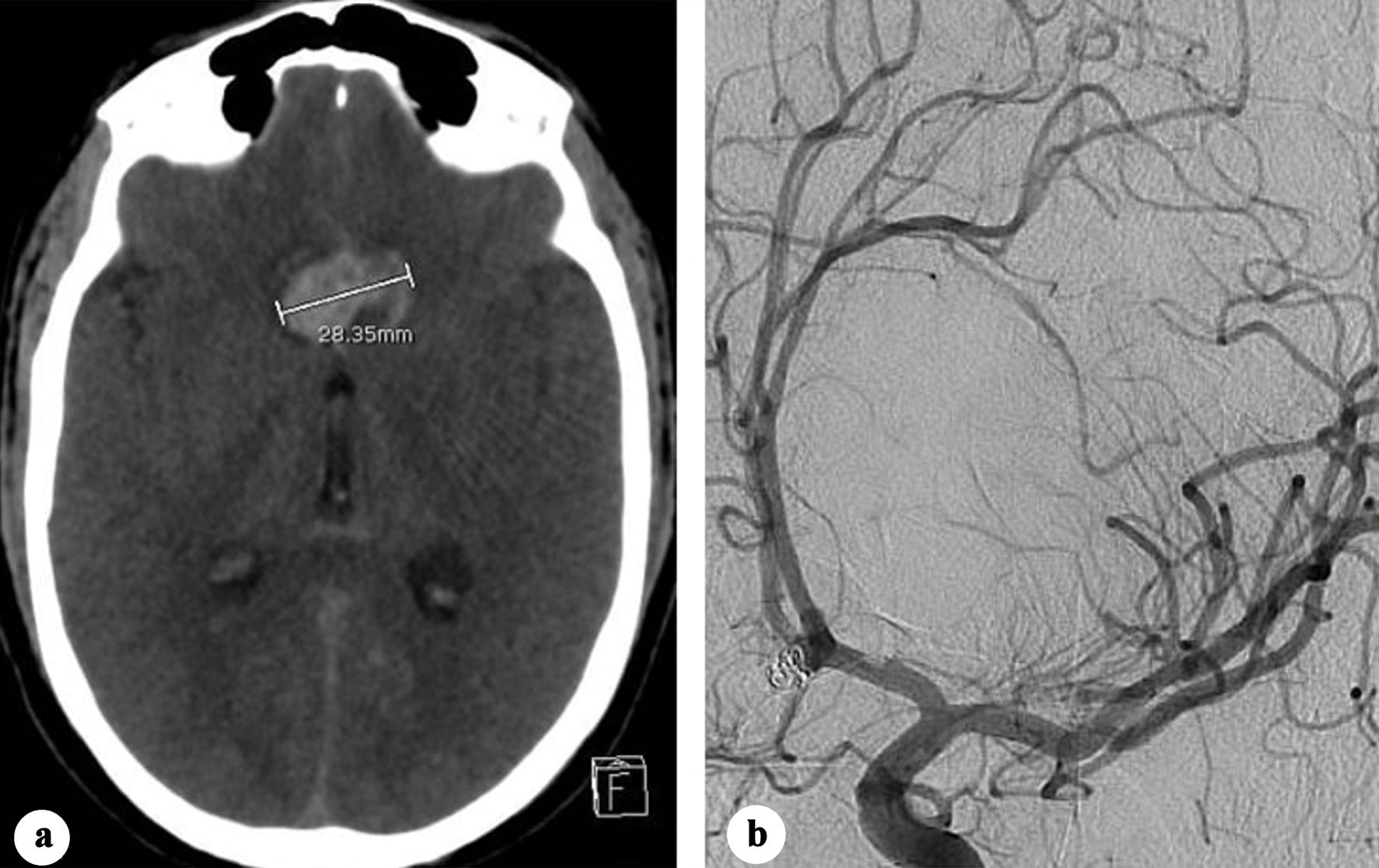

Two days later, the patient developed transient tonic seizures with immediate recovery. CT revealed an 8 mm increase in hematoma size (Fig. 2a). As early aneurysm recanalization was suspected, an emergent cerebral angiography showed no alteration in the morphology of the coil mass, with absence of contrast opacification within it (Fig. 2b). In the absence of associated new subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhage, the hematoma enlargement was attributed to blood redistribution.

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a) Plain CT showing increase in the transverse diameter of the interhemispheric hematoma (28.35 mm). (b) Oblique view two-dimensional (2D) angiography showing no change in the coiled aneurysm morphology. CT: computed tomography. |

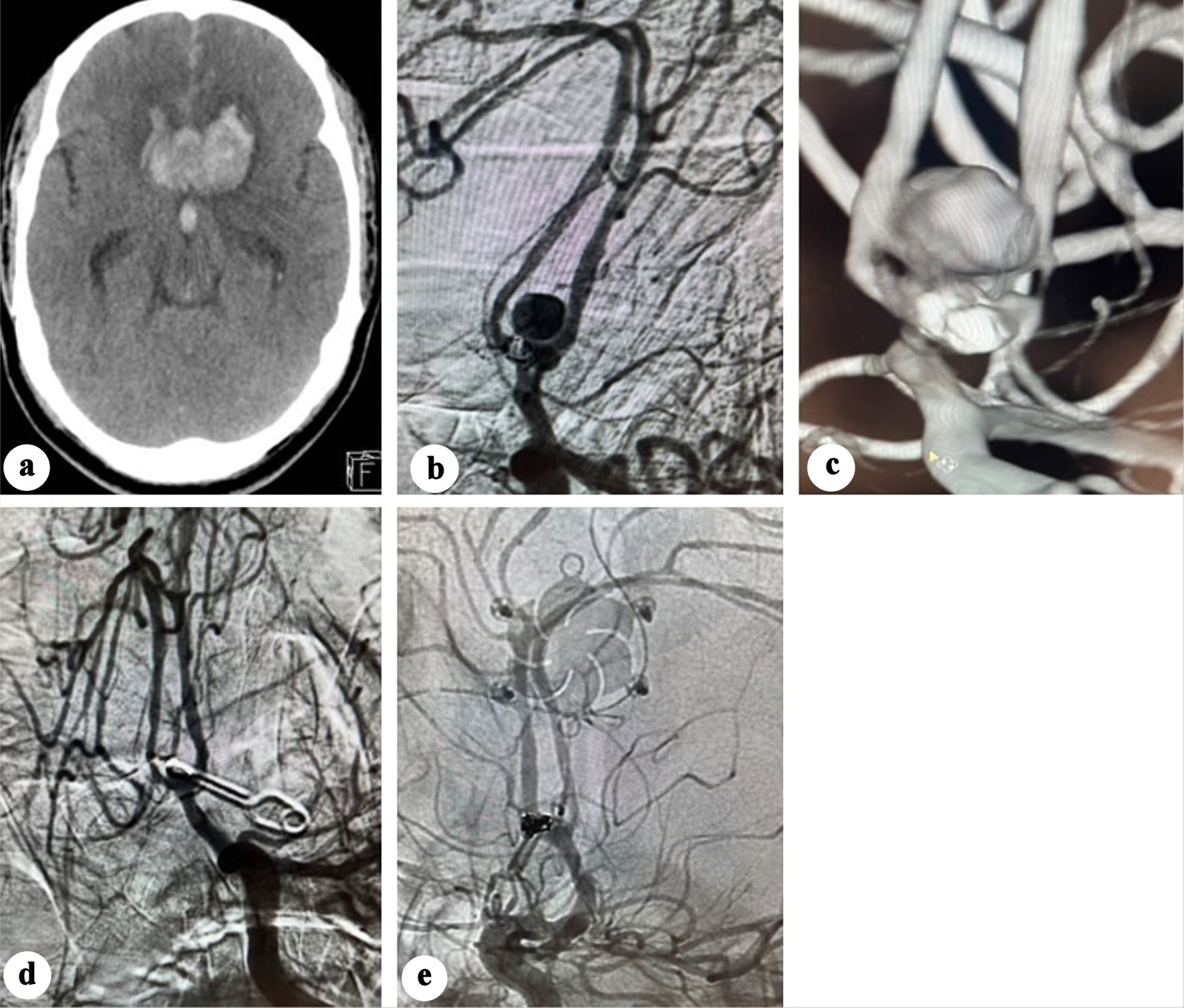

On day 10 post-coiling, the patient had another seizure episode along with decreased consciousness level (GCS 8). CT demonstrated significant rebleed with expansion of the interhemispheric hematoma reaching 38 mm in transverse axis, associated with intraventricular hemorrhage (Fig. 3a). Emergent 2D and 3D angiography identified an 8 mm pseudoaneurysm arising from the posterosuperior ACoA wall, while the coiled aneurysm was morphologically unchanged (Fig. 3b-c).

Click for large image | Figure 3. (a) Plain CT showing significant enlargement of the interhemispheric hematoma. (b) Anteroposterior view angiography showing developing of a pseudoaneurysm. (c) Three-dimensional (3D) angiography showing the development of a pseudoaneurysm opposite the previously coiled aneurysm. (d) Post-clipping subtracted angiography showing disappearance of the pseudoaneurysm. (e) Post-clipping native subtracted angiography showing disappearance of the pseudoaneurysm. CT: computed tomography. |

The pseudoaneurysm was clipped via a left pterional craniotomy, and an external ventricular drain was inserted. Intraoperatively, the pseudoaneurysm was observed as a contained hematoma. Due to the absence of a clearly identifiable neck, the clip was applied as close as possible to the ACoA. Indocyanine green angiography confirmed aneurysm exclusion with preservation of the ACoA patency. Twenty-four hours later, a conventional angiography confirmed disappearance of the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 3d, e).

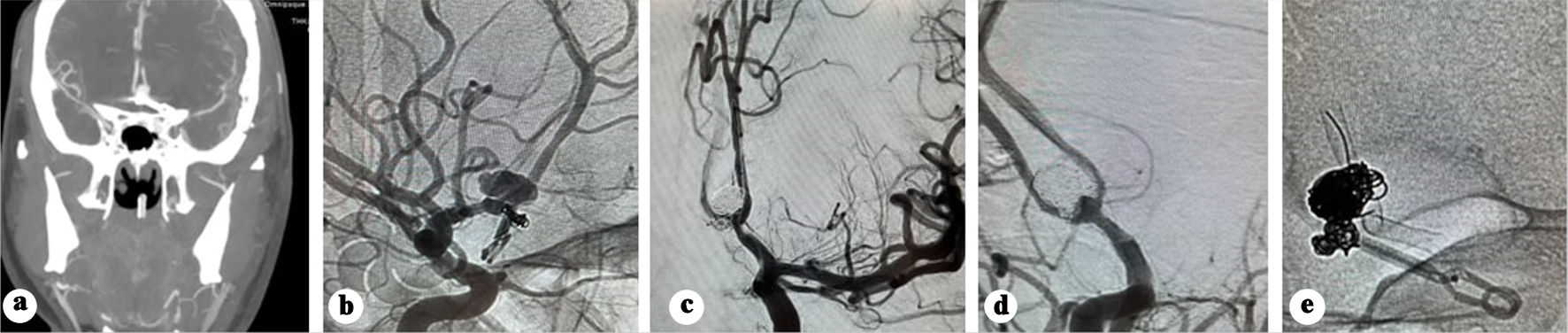

Eight days after clipping, the patient developed sudden headaches associated with right-side hemiplegia. CT, CTA, and CT perfusion showed a bifrontal parasagittal perfusion defect and recurrence of the clipped pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 4a), which was immediately treated with coiling under protection of balloon remodeling, and intra-arterial vasodilator infusion (Fig. 4b, c).

Click for large image | Figure 4. (a) CTA showing recurrence of the pseudo sac post clipping. (b) Native angiography showing recanalization of the pseudoaneurysm. (c) Subtracted angiography post coiling of the pseudoaneurysm. (d) Subtracted angiography showing early recanalization of the pseudoaneurysm base. (e) Native acquisition showing the flow diverter deployed in the left side. CT: computed tomography. |

One week later, the GCS improved to 13, and he regained full motor recovery. Follow-up angiography 9 days post-coiling revealed early recanalization at the pseudoaneurysm base (Fig. 4d). Ticagrelor 180 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg were initiated as a loading dose, and a Silk Vista Baby flow diverter (Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France) was deployed extending from the left A2 to left A1segment (Fig. 4e), covering the irregularity previously noticed in the left A1 segment. Dual antiplatelet regimen (90 mg ticagrelor twice daily (BID) and 100 mg acetylsalicylic acid) was continued for 10 months.

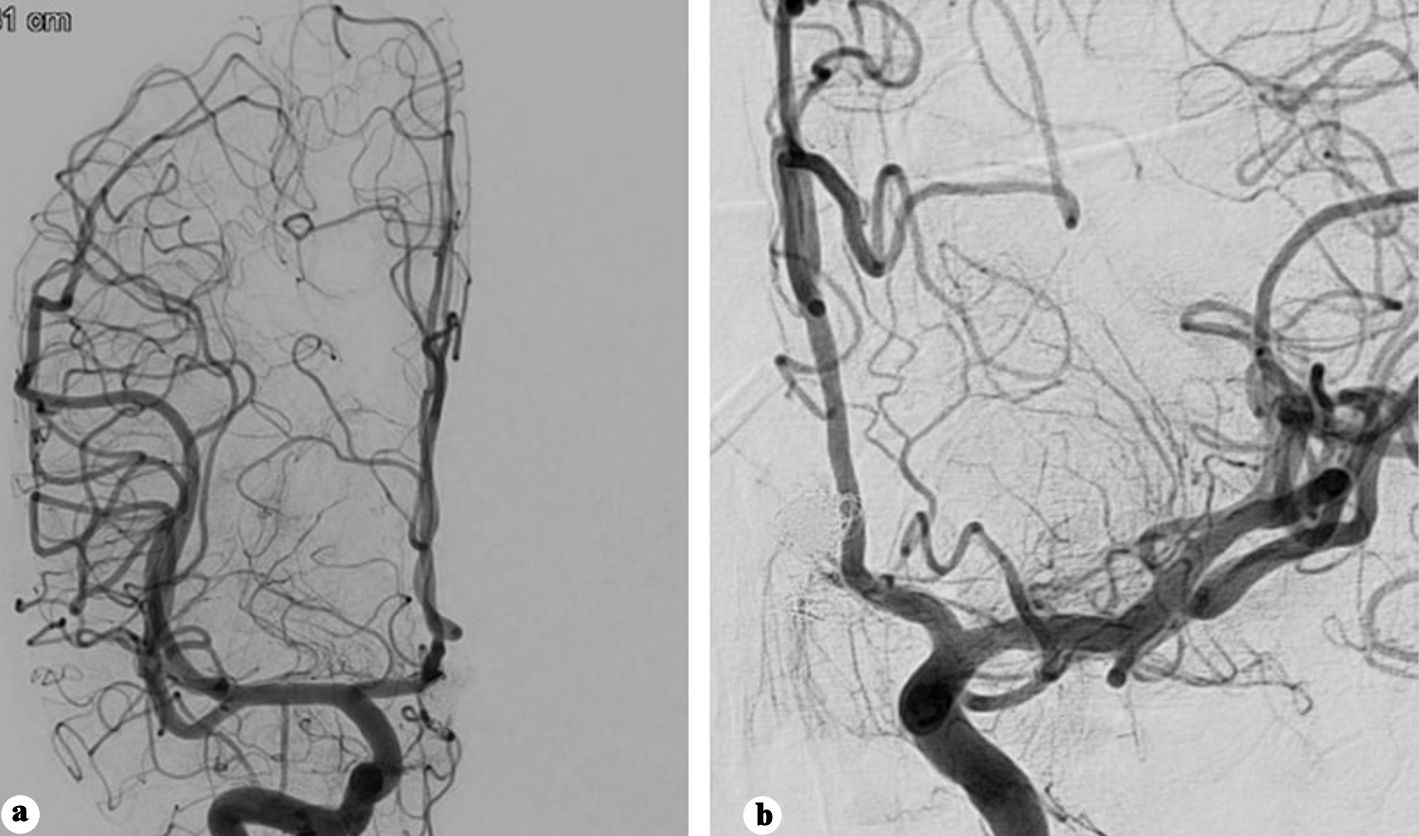

Following a 6-week hospital stay, the patient was discharged in a fully conscious state with no residual deficits. The 10-month follow-up angiography demonstrated a patent flow diverter without evidence of intimal hyperplasia and no residual aneurysm filling (Fig. 5a, b).

Click for large image | Figure 5. (a) Anteroposterior view of right internal carotid angiography showing no filling of the aneurysm. (b) Anteroposterior view of left internal carotid angiography showing no filling of the aneurysm. |

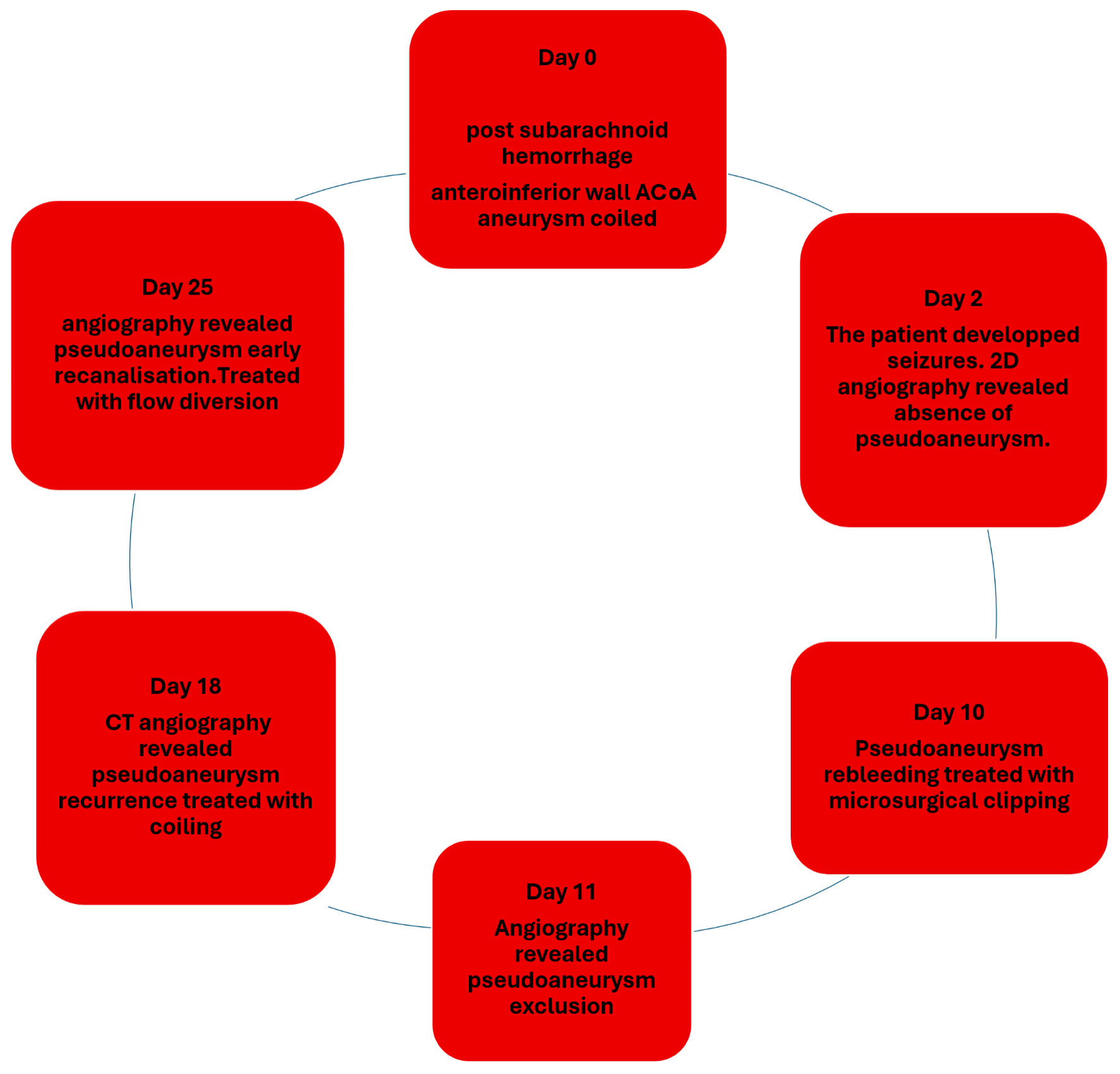

Figure 6 summarizes the chronological sequence of interventions and hemorrhagic events.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Timeline figure summarizing the chronological sequence of interventions and hemorrhagic events. ACoA: anterior communicating artery; CT: computed tomography; 2D: two-dimensional. |

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013 and was approved by the Ethics Board Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case illustrates the early development of a pseudoaneurysm on the opposite wall of a coiled ACoA aneurysm. The patient experienced two subsequent rebleeding episodes, underscoring its aggressive nature and the associated clinical risk. Of particular concern, the angiography studies performed on days 0 and 2 after the initial SAH failed to demonstrate its presence, emphasizing the diagnostic challenge and the need for heightened vigilance in similar scenarios.

Pseudoaneurysms are typically associated with trauma, infection, iatrogenic causes or following true aneurysm or blister rupture. They lack the full complement of arterial wall layers, consisting instead of a wall defect with hematoma contained by adventitia and fibrinous tissue [1], making them prone to rupture and may explain their aggressive course. In our case, the pseudoaneurysm possibly arose from a small blister on the posterosuperior wall, undetected on initial imaging. This could represent a “dumbbell” aneurysm configuration secondary to a potential fragility involving both ACoA walls. This raises the possibility that the aneurysm initially treated was the unruptured component of this aneurysm complex.

Several factors may support this hypothesis. First, there was no predisposing iatrogenic cause: the remodeling balloon used in day 0 remained in the left anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and never crossed into the ACoA, and no intra-procedural perforation or rupture occurred during the uneventful procedure. Second, early follow-up angiography was negative, with no pseudoaneurysm detected either immediately after the initial coiling or on day 2. Third, the irregularity noticed at A1 segment may point to an arterial dysplasia with possible associated fragility, affecting the arterial wall on both sides of the ACoA. This proposed fragility may subject the ACoA wall to a hemodynamic stress, rendering both walls vulnerable to aneurysm formation. The pseudoaneurysm recurrence after clipping may have resulted from a minimal residual neck or incomplete sealing of the blister defect.

ACoA blisters have been previously reported [2, 3]. Kim et al [3] described blister-like ACoA aneurysms developing at mirror locations. The 2D and 3D angiography failed to detect an aneurysm in the ACoA in a 49- year- old man presented with SAH. A blister aneurysm was detected intraoperatively, and the hole created by its rupture was repaired with microsuture technique. This patient rebled 14 days post-surgery, the emergent angiography failed to reveal recanalization or de novo aneurysm. Surgical exploration revealed no change in the previously treated blister while a de novo blister developed on the opposite wall and was treated with microsurgical clipping of the bleeding point of the ACoA [3].

This case scenario may support our hypothesis that the pseudoaneurysm that developed in this report was a result of a blister rupture, which was either occult in the 2D angiography studies or as a de novo lesion.

Disappearance and reappearance of aneurysms have been reported in several cases. Nakajima et al [4] described an A2-A3 junction aneurysm detected in a CTA study on day 0 post SAH, absent on angiography 6 h later, partially reappearing on day 11, and fully visualized by day 19. Jayakumar et al [5] reported a ruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysm that disappeared after the initial angiogram and reappeared 3 months later. Spetzler et al described a frontopolar artery aneurysm disappearing and reappearing over 23 days post-SAH [6].

Proposed mechanisms for intermittent aneurysm visibility include the use of antifibrinolytic therapy [6], spontaneous thrombosis in narrow-neck large or giant aneurysms with subsequent slow turbulent flow [7], vasospasm [6], and intraoperative hypotension [8]. Nakajima et al suggested that a narrow-elongated neck with surrounding clot could induce temporary thrombosis [4], while Kim et al linked the induced hypotension during anesthesia to the reduction of the intra-aneurysmal circulation [8].

In our case, spontaneous temporary occlusion of a blister might be a plausible interpretation with possible contribution of the general anesthesia-induced hypotension, favoring reduction and slowing of the intra blister circulation. When this blister ruptured, it allowed subsequent development of a pseudoaneurysm reflecting the inherent fragility of the arterial wall.

Following the first suspected rebleed, the angiography study did not include a rotational angiography, as we focused on the possibility of early post-coiling recanalization. This may have resulted in failure to detect a blister or small pseudoaneurysm developing on the opposite wall of the coiled aneurysm. Rotational angiography can detect aneurysms < 3 mm that may be missed on 2D studies, as demonstrated by van Rooij et al, who found 94 additional aneurysms in 3D reconstructions in a study including 350 patients, 27 of which were missed even by experienced neuroradiologists, while 26 of these were less than 3 mm [9]. Neurointerventionalists should be aware of a possible hidden cause of rebleeding even with a negative angiography. Early detection using repeated conventional 2D and notably 3D angiography can depict small aneurysms and may help in ruling out a newly developed or a previously angiographically occult aneurysm.

Treatment of pseudoaneurysm in the ACoA is challenging, as conventional coiling or clipping may be associated with early recurrence. Direct repair of the wall defect either by microsuturing or targeted clipping may provide a more durable alternative.

Flow diversion played an important therapeutic role in treatment of this case, which, to our knowledge, is the first where a flow diverter was used to treat a pseudoaneurysm located in the ACoA. As treatment of pseudoaneurysms with microsurgical clipping and endovascular treatment using coils is technically challenging, flow diverters may offer an alternative way for treatment. The Silk Vista Baby is a low-profile flow diverter which is delivered through a 17 microcatheter and could be used for small sized artery ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 mm. It is made of 48 braided wires making its porosity optimal for flow diversion while keeping good resilience to adapt in such small sized arteries. Its dense mesh struts promote thrombosis in the pseudoaneurysm and act as a scaffold enhancing endothelial growth and neointima formation. Greco et al [10] conducted a meta-analysis including studies for pseudoaneurysms treated with flow diverters. They reported eight studies including 85 pseudoaneurysms, of which 77.6% were located in the ICA, while 11.8% were located in the vertebral artery. The short-term (less than 1 year) complete occlusion rate was 79% while the long-term (more than 1 year) occlusion rate was 84%. They found 12% risk of symptomatic thromboembolic complications with 14% overall mortality rate. Flow diverters were previously reported in treating intra dural aneurysms located in the middle cerebral artery (MCA). Theocharidou et al [11] used flow diverter to treat postoperative pseudoaneurysm in the MCA, which disappeared in the 6-month follow-up angiography. Gelman et al treated an MCA pseudoaneurysm following a gunshot using flow diverter. The aneurysm was completely occluded in the 4-month follow-up angiography [12]. Because the use of flow diverters requires antiplatelet therapy, their deployment in the acute phase should be approached with caution due to the potential hemorrhagic complications. Cagnazzo et al found a 4% risk of rebleeding in their meta-analysis of 223 patients with ruptured aneurysms treated with flow diverters [13].

Use of flow diversion may provide durable treatment for cerebral intra dural pseudoaneurysms; however, larger studies are warranted to validate its efficiency and safety.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Interventional Neuroradiology (INR) and neurosurgery teams.

Financial Disclosure

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The case was fully deidentified, and all data was anonymized; therefore, the requirement for informed consent was not required.

Author Contributions

Mostafa Mahmoud: primary author, concept and design, manuscript drafting, overall responsibility. Muhammad Mohsin Khan: data collection, critical revision and final approval. Osman Koc: data collection, critical revision and final approval. Ehab Mahmoud: data collection, critical revision and final approval. Sirajeddin Belkhair: data collection, critical revision and final approval.

Data Availability

The authors declare that all relevant clinical data supporting the report are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Ishikawa T, Nakamura N, Houkin K, Nomura M. Pathological consideration of a "blister-like" aneurysm at the superior wall of the internal carotid artery: case report. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(2):403-405; discussion 405-406.

doi pubmed - Andaluz N, Zuccarello M. Blister-like aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery: a retrospective review of diagnosis and treatment in five patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(4):807-811; discussion 811.

doi pubmed - Kim M, Park J. Successive development and rupture of blister-like anterior communicating artery aneurysms at mirror locations. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2024;67(6):675-681.

doi pubmed - Nakajima Y, Yoshimine T, Mori H, Nakamuta K, Fujimura I, Sakashita K, Kohmura E, et al. Spontaneous disappearance and reappearance of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm: one case found in a group of 33 consecutive patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage who underwent repeat angiography. Neurol Res. 2000;22(6):583-587.

doi pubmed - Jayakumar PN, Ravishankar S, Balasubramaya KS, Chavan R, Goyal G. Disappearing saccular intracranial aneurysms: do they really disappear? Interv Neuroradiol. 2007;13(3):247-254.

doi pubmed - Spetzler RF, Winestock D, Newton HT, Boldrey EB. Disappearance and reappearance of cerebral aneurysm in serial arteriograms. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1974;41(4):508-510.

doi pubmed - Brownlee RD, Tranmer BI, Sevick RJ, Karmy G, Curry BJ. Spontaneous thrombosis of an unruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. An unusual cause of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1995;26(10):1945-1949.

doi pubmed - Kim HJ, Kim JH, Kim DR, Kang HI. Thrombosis and recanalization of small saccular cerebral aneurysm : two case reports and a suggestion for possible mechanism. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;55(5):280-283.

doi pubmed - van Rooij WJ, Sprengers ME, de Gast AN, Peluso JP, Sluzewski M. 3D rotational angiography: the new gold standard in the detection of additional intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(5):976-979.

doi pubmed - Greco E, Rios-Zermeno J, Ghaith AK, Faisal UH, Goyal A, Akinduro OO, Kashyap S, et al. Flow diversion using the Pipeline embolization device for intracranial and extracranial pseudoaneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2023;54(5):E5.

doi pubmed - Theocharidou A, Spanou A, Alexandratou M, Michas V, Lamprou V, Psoma E, Finitsis S. An off-label use of flow-diverter stent as a successful treatment of a postoperative middle cerebral artery pseudoaneurysm. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18(6):2219-2223.

doi pubmed - Gelman JC, Shutran M, Young M, Taussky P, Vega RA, Armonda R, Ogilvy CS. Flow diversion of a middle cerebral artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to a gunshot wound: a case report. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2023;25(4):434-439.

doi pubmed - Cagnazzo F, di Carlo DT, Cappucci M, Lefevre PH, Costalat V, Perrini P. Acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms treated with flow-diverter stents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(9):1669-1675.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.