| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jnr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 4, December 2025, pages 172-181

Mortality Following Intracerebral Hemorrhage After Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Decision Tree-Based Classification Approach

Bongkot Wijitjarassanga , Thanin Lokeskraweea, e

, Natthaphon Pruksathorna

, Jarupa Yaowalaornga

, Suppachai Lawanaskolb

, Jayanton Patumanondc, Wanwisa Bumrungpagdeed

, Suwapim Chanlaord

, Chawalit Lakdeed

aDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Lampang Hospital, Lampang 52000, Thailand

bChaiprakarn Hospital, Chiang Mai 50320, Thailand

cClinical Epidemiology and Clinical Statistics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok 65000, Thailand

dDepartment of Radiology, Buddhachinaraj Phitsanulok Hospital, Phitsanulok 65000, Thailand

eCorresponding Author: Thanin Lokeskrawee, Department of Emergency Medicine, Lampang Hospital, Lampang 52000, Thailand

Manuscript submitted October 1, 2025, accepted December 3, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: Mortality After Post-Thrombolysis ICH

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr1055

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) after intravenous (IV) alteplase in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) can be assessed clinically as asymptomatic ICH (asICH) or symptomatic ICH (sICH) according to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II (ECASS II) definition, and radiographically as hemorrhagic infarction types 1-2 (HI1-2) or parenchymal hematoma types 1-2 (PH1-2). Reported mortality in sICH ranges from 7.8% to 42.8%, with PH2 carrying the highest risk, up to 50%. Although some patients may benefit from neurosurgical intervention, the prognostic overlap between clinical and radiographic classifications remains unclear. A decision tree approach may clarify mortality risk across subgroups and aid early triage.

Methods: This prognostic descriptive study employed a retrospective cohort design at the Stroke Center, Lampang Hospital. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with AIS who received IV alteplase between January 2017 and December 2024 were included. A decision tree framework was constructed to examine 7-day mortality, incorporating clinical classification, radiographic subtype, and neurosurgical intervention as decision nodes.

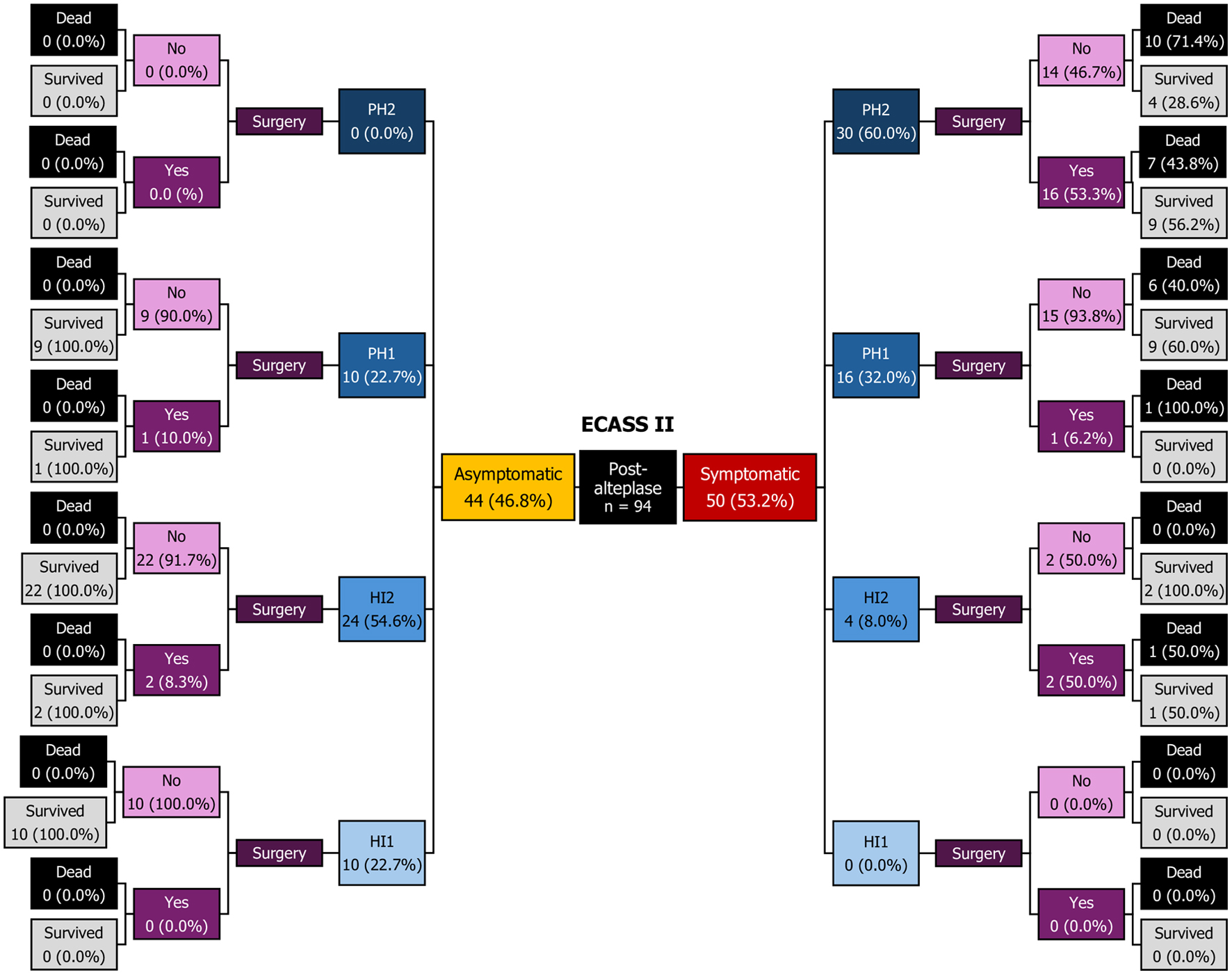

Results: Among 94 patients, asICH occurred in 44 (46.8%) and sICH in 50 (53.2%). In the asICH group, HI2 was the predominant subtype (24/44, 54.6%) and all survived. In the sICH group, PH2 was the leading subtype (30/50, 60.0%). Mortality was influenced by surrogate compliance with neurosurgical advice: refusal of surgery after recommendation resulted in 100% mortality, whereas acceptance reduced mortality to 43.8% (P = 0.043).

Conclusion: Post-alteplase ICH had a 7-day mortality of 27%. The decision tree framework offered a simple visualization for early risk stratification and may help support clinical decision-making.

Keywords: Decision trees; Prognosis; Ischemic stroke; Tissue plasminogen activator; X-ray computed tomography; Intracranial hemorrhages

| Introduction | ▴Top |

For patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) presenting to the emergency department (ED) within 3 to 4.5 h, the standard treatment remains intravenous (IV) thrombolysis with alteplase [1], which can be administered in rural hospitals equipped with computed tomography (CT). The benefit of alteplase is further enhanced when combined with mechanical thrombectomy (MT) [2]. Additionally, MT has demonstrated benefit in selected patients presenting within an extended time window of 6 to 12 h [3]. In Thailand, MT is limited to designated stroke centers, where specialist availability remains scarce. At Lampang Hospital, a regional stroke center in northern Thailand, MT is available only from 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM, reflecting resource limitations as the procedure is supported by only one neurointerventionist. Consequently, the majority of AIS patients are treated with IV alteplase. A previous study reported the prevalence of post-alteplase intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) to be 21.2% [4].

Post-alteplase ICH can be evaluated from two dimensions. First, the clinical classification includes symptomatic ICH (sICH) and asymptomatic ICH (asICH), based on varying definitions such as those of National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II (ECASS II), and modified Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (mSITS-MOST) [5]. Second, the radiographic classification consists of hemorrhagic infarction (HI1, HI2) and parenchymal hematoma (PH1, PH2) [6]. A prior study reported the prevalence of asICH as 13.1% and sICH as 8.1% [4], while radiographic subtypes were distributed as 89% HI and 11% PH [7].

The reported 3-month mortality associated with sICH ranges from 7.8% to 42.8% [8, 9], depending on the definition and classification domain. The prevalence of mortality in PH2 has been reported to be as high as 50% [10]. In clinical practice, some patients with sICH experience neurological deterioration despite minimal ICH on CT, often due to brain edema. Conversely, PH1 can present without symptoms. These observations highlight the prognostic uncertainty inherent in current classifications. Furthermore, a 3-month follow-up may be confounded by non-neurological complications such as ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), urinary tract infection (UTI), pressure ulcers, and sepsis. Therefore, this study aimed to describe and visualize 7-day mortality using clinical and radiographic classifications through a decision tree approach [11].

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

This prognostic descriptive study used a retrospective, cross-sectional observational design conducted in the Stroke Unit of Lampang Hospital, a regional stroke center in northern Thailand equipped with MT services. The unit includes 16 stroke beds and eight intensive care beds dedicated to stroke care. The study period spanned January 2017 to December 2024. A descriptive decision tree framework was applied solely to visualize and summarize outcome patterns across prespecified subgroups, rather than to generate predictive estimates. Sequential decision nodes reflected the clinical and radiographic hierarchy: 1) sICH vs. asICH; 2) radiographic classification (HI1, HI2, PH1, PH2); and 3) neurosurgical intervention (yes vs. conservative treatment).

Participants and data collection

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older who developed ICH after receiving IV alteplase were included. Those with a final diagnosis classified as Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) subtypes 4 or 5 [12] were excluded due to different mechanisms of hemorrhage.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 7-day mortality (yes/no) following post-alteplase ICH, selected to capture early pathophysiologic mortality driven by hematoma expansion, perihematomal edema, mass effect, and acute neurological deterioration, rather than later deaths influenced by downstream medical or long-term care-related complications.

Exposure

All patients received full-dose IV alteplase, consequently developing ICH.

Definitions and measurement criteria

Clinical classification of sICH (mSITS-MOST window period was modified in this study) includes: 1) NINDS definition: any hemorrhagic transformation temporally associated with any neurological worsening, even if minor and not reflected in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score. Window period: within 7 days [13]. 2) ECASS II definition: any ICH with a ≥ 4-point increase in the NIHSS, and hemorrhage judged the likely cause of deterioration. Window period: within 7 days [1, 14]. 3) mSITS-MOST definition: presence of PH on neuroimaging, accompanied by a ≥ 4-point worsening on the NIHSS or death within 24 h. In this study, we modified the window period to 7 days for consistency with the other definitions [15].

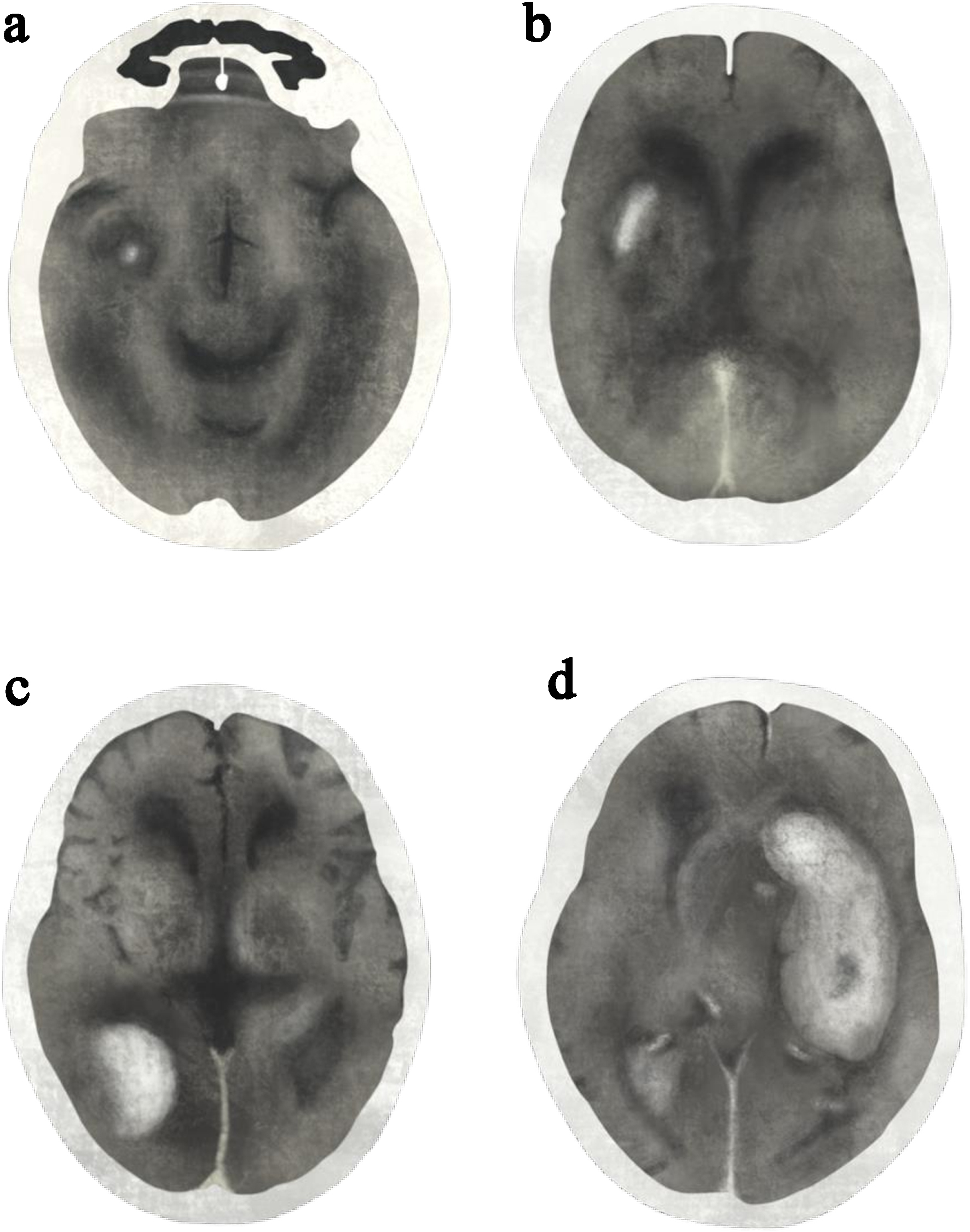

Radiographic classification [16] includes: 1) HI1: small petechial hemorrhages at the infarct margins, without mass effect. 2) HI2: confluent petechial hemorrhages throughout the infarcted region, without mass effect. 3) PH1: hematoma involving ≤ 30% of the infarcted area, with mild mass effect. 4) PH2: hematoma involving > 30% of the infarcted area, with substantial mass effect (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Post-alteplase intracerebral hemorrhage classified by radiographic classifications: (a) hemorrhagic infarction type 1 (HI1), (b) hemorrhagic infarction type 2 (HI2), (c) parenchymal hematoma type 1 (PH1), and (d) parenchymal hematoma type 2 (PH2). Illustration drawn and modified from the original reference [16]. |

TOAST classification [12] subtypes include: 1) large-artery atherosclerosis (embolus/thrombosis); 2) cardioembolism (high-risk/medium-risk sources); 3) small-vessel occlusion (lacune); 4) stroke of other determined etiology (e.g., dissection, hypercoagulable states); and 5) stroke of undetermined etiology (negative evaluation, incomplete evaluation, or two or more causes identified).

Data collection

Clinical, radiographic, and outcome data were retrospectively extracted from the electronic medical records (EMR) and imaging archive system at Lampang Hospital. Data included baseline characteristics, NIHSS, alteplase administration, stroke subtype (TOAST), ICH classification (clinical and radiographic), neurosurgical intervention, and 7-day mortality. All variables were recorded using a standardized data collection form by trained abstractors. Discrepancies in clinical classification were resolved by consensus among three emergency physicians (clinical team), who each performed blinded independent evaluations. Radiographic classification was likewise assessed by three radiologists (radiographic team) under the same blinded conditions. Both teams conducted their assessments separately.

Bias

Information bias

Data were retrospectively extracted from routine records, with potential variability in clinical documentation by physicians and nurses, particularly regarding NIHSS scores and neurological deterioration.

Misclassification bias

Retrospective classification using clinical (NINDS, ECASS II, mSITS-MOST) and radiographic (HI1-PH2) criteria may lead to errors, for example, clinical deterioration from brain edema with only HI1 on imaging could be misclassified as sICH, or confluent petechiae may be mistaken for a small hematoma, leading to ambiguity between HI2 and PH1.

Study size estimation

Even though this was a descriptive study, estimating sample sizes was crucial, particularly for the parameters represented in the decision tree nodes, including both clinical and radiographic classifications. For the clinical classification, the estimated mortality for asICH was 15% (85% survival), corresponding to a survival-to-death ratio of 5:1. Using a two-sided test with alpha < 0.05 and 80% power, this required five deaths and 25 survivors, totaling 30 asICH cases. For sICH (30% mortality, 70% survival), a survival-to-death ratio of 2:1 required 21 deaths and 42 survivors, totaling 63 cases. Subgroup requirements for the radiographic classifications (HI1, HI2, PH1, and PH2) were also determined (Supplementary Material 1, jnr.elmerpub.com).

Quantitative variables

Variables used as decision nodes in the decision tree were handled as categorical inputs and reported using counts and proportions as n (%). These included: clinical classification (sICH vs. asICH); radiographic classification (HI1, HI2, PH1, PH2); and treatment approach (neurosurgical intervention vs. conservative treatment).

All classifications were applied using established criteria (e.g., NINDS, ECASS II, and mSITS-MOST definitions). No continuous variables were modeled or arbitrarily grouped.

Statistical methods

This was a single-group descriptive study with no comparative statistical analysis. Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage, n (%), while continuous variables were summarized using mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range (IQR)), depending on data distribution. The three decision nodes - clinical classification, radiographic classification, and neurosurgical intervention - were presented as n (%). Family decision, reflecting whether surrogates accepted or declined surgery based on neurosurgical recommendations, was treated as an effect modifier and explored through sensitivity analysis.

This study was registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) under the identifier TCTR20250827015. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Lampang Hospital (CERT No. 077/68), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the observational design. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [17].

| Results | ▴Top |

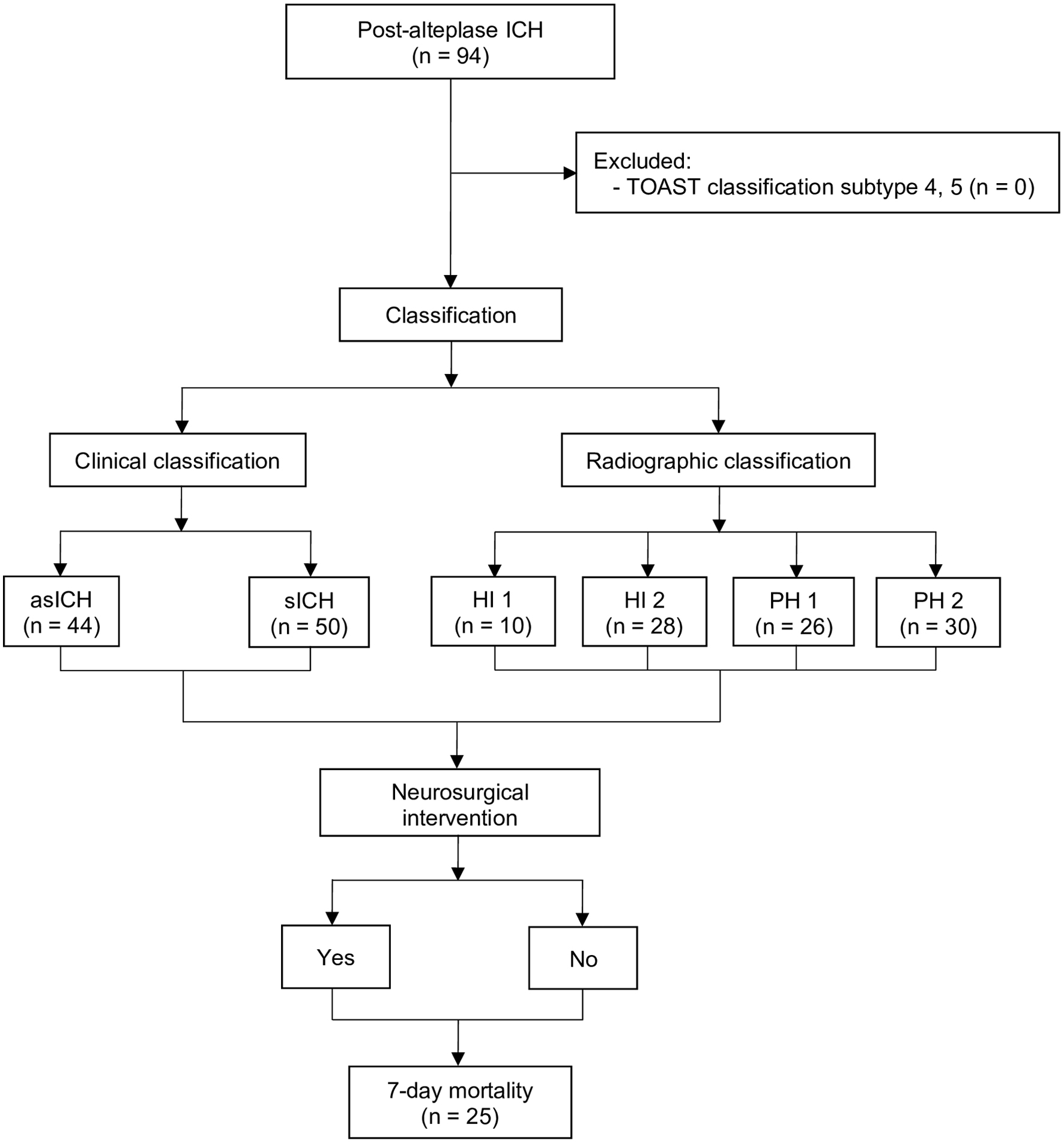

From January 2017 to December 2024, 94 patients developed post-alteplase ICH, with no exclusions. Classification was performed in two ways: 1) clinical, based on the ECASS II definition [1, 14], yielding 44 asICH and 50 sICH cases; and 2) radiographic, comprising 10 HI1, 28 HI2, 26 PH1, and 30 PH2 cases. Following consideration of neurosurgical intervention, 7-day mortality was assessed, with 25 deaths and 69 survivors (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Study flow diagram. asICH: asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; HI: hemorrhagic infarction; ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; PH: parenchymal hematoma; sICH: symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; TOAST: Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. |

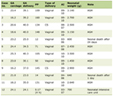

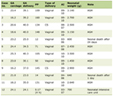

Older age and higher initial NIHSS scores were more frequent in the death group (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Post-Alteplase Intracerebral Hemorrhage Stratified by Survival Status |

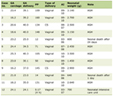

To maintain consistency with the subsequent analyses, radiographic classifications are presented first, followed by clinical classifications. Increasing radiographic severity corresponded to higher mortality. Interestingly, PH1 demonstrated an almost equal distribution between deaths and survivors (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Radiographic Classifications of Post-Alteplase Intracerebral Hemorrhage Stratified by Survival Status |

Across NINDS, ECASS II, and mSITS-MOST, sICH similarly led to death in approximately 50% (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Clinical Classifications of Post-Alteplase Intracerebral Hemorrhage Stratified by Survival Status |

To determine which definition to apply, we compared the proportion of sICH assessed blindly by three emergency physicians: 54.3% for NINDS, 53.2% for ECASS II, and 52.1% for mSITS-MOST (P = 0.958). ECASS II was selected for subsequent decision tree analysis, as it is widely used in prior research [18], demonstrates the highest interrater agreement [19], and has been previously applied within Thai clinical practice [20] (Table 4).

Click to view | Table 4. Proportion of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhages Across Clinical Definitions |

Decision tree approach

Starting with clinical classification, sICH and asICH each accounted for 50% of cases. Within the asICH group, HI2 was the most common subtype (54.6%): 91.7% received conservative management and survived, while two patients underwent neurosurgical intervention and also survived. PH2 was not observed. PH1 occurred in 22.7% of asICH cases: 90% of PH1 were treated conservatively and survived, while one patient underwent neurosurgical intervention with survival. HI1 accounted for the remaining 22.7% of asICH cases, all managed conservatively with survival.

In the sICH group, PH2 was the most common subtype (60%), with cases evenly divided between conservative management and neurosurgical intervention: mortality was 71.4% with conservative treatment but decreased to 43.8% following surgery. PH1 comprised approximately one-third of sICH cases, with 93.8% treated conservatively and an overall mortality of 40%. HI2 accounted for 8% of sICH cases: treatment was equally split between conservative and surgical approaches, with all conservatively managed patients surviving, while one surgically treated patient died from sepsis. No cases of HI1 were observed (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Decision tree diagram. ECASS II: European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II; HI: hemorrhagic infarction; PH: parenchymal hematoma; Sx: surgery. |

Specific group analysis

In the PH2 subgroup (n = 30), mortality differed according to the concordance between neurosurgeons’ recommendations and surrogates’ decisions. If surgery was advised but refused, all four patients died (100%). Conversely, when surgery was advised and accepted, seven of 16 patients died (43.8%), showing that compliance with the neurosurgeon’s recommendation was associated with a lower proportion of deaths (P = 0.043). When conservative management was advised, 10 surrogates complied and six patients died (60.0%). No cases occurred where surgery was requested against a conservative recommendation (Table 5).

Click to view | Table 5. Surrogates’ Decisions and 7-Day Mortality According to Neurosurgeon’s Suggestion |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Key results

Among all patients with post-alteplase ICH (n = 94), there were 25 deaths, corresponding to a 7-day mortality of 27%. Mortality increased with radiographic severity, with PH2 showing the highest risk. The decision tree framework clearly illustrated prognostic patterns by combining clinical and radiographic classifications with treatment decisions. In the PH2 subgroup, when surgery was suggested but refused, all patients died (100%). Conversely, when surgery was suggested and accepted, the proportion of deaths decreased to 43.8%, indicating that compliance with the neurosurgeon’s suggestion was associated with improved survival.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a retrospective study, data relied on existing medical records, which may have been incomplete or inconsistently documented, particularly regarding NIHSS scores and subtle neurological deterioration. Second, misclassification bias may have occurred because retrospective application of NINDS, ECASS II, and mSITS-MOST definitions could not fully capture clinical nuances, and distinguishing between HI2 and PH1 on imaging was occasionally ambiguous. Third, although this was a descriptive study, study size calculation remained important; while the achieved sample size was sufficient for clinical classification (94 vs. 93 estimated), the radiographic subgroups were underpowered (94 vs. 150 estimated), particularly across all categories, which may have reduced the precision of mortality estimates (Supplementary Material 2, jnr.elmerpub.com). Finally, although mortality differences in PH2 patients appeared related to surrogates’ decisions and compliance with the neurosurgeon’s suggestion, this association cannot establish causation because potential confounding factors were not fully controlled.

Interpretation

We selected 7-day mortality rather than 30- or 90-day outcomes to focus on deaths directly attributable to post-alteplase ICH, reflecting early pathophysiologic mortality and minimizing the confounding effect of later complications such as infection. In contrast, most previous studies reported 30- or 90-day mortality for comparability with functional outcomes measured by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), which explains the discrepancy in reporting periods. Because few studies have used a 7-day endpoint, direct comparisons are limited. Another difference is that prior reports often presented mortality among all alteplase-treated patients, whereas our denominator was restricted to those who developed post-alteplase ICH, consistent with our research domain.

Radiographic subtypes in our cohort also differed substantially compared with a previous Thai study. Using all post-alteplase ICH cases (n = 94) as the denominator, PH2 accounted for 31.9% (30/94), essentially equal to 32.1% (26/81) in the reference cohort. PH1 was slightly higher in our series at 27.7% (26/94) compared with 21.0% (17/81), whereas HI1 + HI2 was slightly lower at 40.4% (38/94) versus 46.9% (38/81) [21] (Table 6).

Click to view | Table 6. Comparison of NIHSS Categories Across Radiographic Classifications Between Lampang and Saraburi Cohorts |

In our cohort, overall, 7-day mortality was 27% (25/94); however, this figure cannot be directly compared with most studies, which typically report 30- or 90-day outcomes. Notably, the Lancet meta-analysis did not provide overall mortality but focused specifically on fatal ICH, defined as PH2 leading to death within 7 days, aligning with the short-term follow-up period used in our study. For PH2, our 7-day mortality was 56.7% (17/30), higher than the 39.4% (91/231) reported in that meta-analysis [22]. This concordance in outcome window highlights the potential value of a 7-day endpoint for future research aiming to emphasize early pathophysiologic mortality.

The higher proportions of PH2 and PH1 in our cohort persisted even after exploring baseline stroke severity. When NIHSS was categorized into 4 - 15, 16 - 20, and > 20, the distribution of severe stroke (NIHSS > 20) among PH2 patients was comparable between our study and the Thai reference (20.0% vs. 23.1%). However, a striking difference was observed in less severe strokes (NIHSS 4 - 15), where PH2 accounted for 56.7% (17/30) in our study versus only 19.2% (5/26) in the same report [21]. This disproportion suggests that PH2 occurred more frequently even among patients with milder symptoms in our cohort, a finding that warrants systematic evaluation using causal inference methodologies in future research (Table 6).

To ensure the interpretability and robustness of our findings, the structure of the decision tree followed a prespecified clinical hierarchy rather than data-driven or algorithmic splitting. Clinical classification (asICH vs. sICH) was placed at the first node because symptom evolution and neurological worsening are the earliest clinical determinants of prognosis. Radiographic severity (HI1-PH2) was positioned second, reflecting its established pathophysiologic gradient in hematoma expansion, mass effect, and early neurological decline. Neurosurgical intervention formed the final node, representing a downstream treatment decision that is directly shaped by the clinical and imaging findings that precede it. This ordered sequence mirrors real-world clinical decision-making and minimizes arbitrary structuring, supporting the robustness of the descriptive patterns observed across the terminal nodes.

Shared decision making (SDM) offers an ethical and policy context for interpreting the differences between families who accepted vs. declined neurosurgical intervention. SDM emphasizes relational autonomy, where decisions arise from communication and understanding between clinicians and surrogates, not solely from information disclosure [23]. In Thailand, universal health coverage eliminates financial barriers, so treatment refusal did not reflect socioeconomic inequity. Instead, many surrogate decisions were influenced by concerns about long-term caregiving capacity, as families may be unable to provide continuous care for patients expected to survive with severe disability. Conversely, when clinical prognosis was extremely poor, SDM enabled families to align treatment choices with the patient’s values. These contextual factors help explain surgical decision-making patterns without implying disparities in access to care.

Generalizability

Although this was a single-center study, patients’ characteristics may differ from those in other stroke centers. MT was available at our institution but was excluded to isolate the effect of IV alteplase, as combined therapy may yield different bleeding patterns. The strength of this study stems from its decision tree framework, which provides a transparent and clinically intuitive way to classify post-alteplase ICH and anticipate short-term outcomes. Because it relies on routinely available clinical and imaging variables, this approach may be applicable beyond our center, but confirmation in multicenter cohorts is required to establish broader generalizability.

Conclusion

In this retrospective study of post-alteplase ICH cases, 7-day mortality was 27%, with the highest risk observed in patients with PH2 hemorrhage. Mortality reached 100% in PH2 cases when surgery was declined, but dropped to 43.8% when surgery was accepted, underscoring the importance of neurosurgical decision-making. The descriptive decision tree framework integrating clinical type, radiographic subtype, and treatment decisions provides a clear visualization of early risk patterns and may support clinical discussions and early management planning.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Sample size estimation for clinical and radiographic classifications.

Suppl 2. Comparison of estimated and achieved sample sizes for clinical and radiographic classifications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Emergency Medicine residents, staff, and registered nurses at the Department of Emergency Medicine, Lampang Hospital. We acknowledge the assistance of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for its support in translating and refining the manuscript into English.

Financial Disclosure

The study was supported by Lampang Medical Education Center.

Conflict of Interest

The authors reported no contents in the article as conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was waived due to the observational nature of the study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Bongkot Wijitjarassang, Thanin Lokeskrawee, Suppachai Lawanaskol, and Jayanton Patumanond. Data curation: Bongkot Wijitjarassang. Formal analysis: Natthaphon Pruksathorn, Jarupa Yaowalaorng, Suwapim Chanlaor, Wanwisa Bumrungpagdee, Chawalit Lakdee, Thanin Lokeskrawee, Suppachai Lawanaskol, and Jayanton Patumanond. Methodology: Bongkot Wijitjarassang, Thanin Lokeskrawee, Suppachai Lawanaskol, and Jayanton Patumanond. Supervision: Thanin Lokeskrawee, Suppachai Lawanaskol, and Jayanton Patumanond. Writing - original draft: Bongkot Wijitjarassang and Thanin Lokeskrawee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

AIS: acute ischemic stroke; asICH: asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; CT: computed tomography; ECASS II: European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II; ED: emergency department; EMR: electronic medical record; HI: hemorrhagic infarction; ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; IQR: interquartile range; IV: intravenous; mSITS-MOST: modified Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study Definition; MT: mechanical thrombectomy; NA: not applicable; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NINDS: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; PH: parenchymal hematoma; SD: standard deviation; SDM: shared decision making; sICH: symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage; STROBE: Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; TCTR: Thai Clinical Trials Registry; TOAST: Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment; UTI: urinary tract infection; VAP: ventilator-associated pneumonia

| References | ▴Top |

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1317-1329.

doi pubmed - Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Treurniet KM, Chen W, Peng Y, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981-1993.

doi pubmed - Dharmasaroja P, Ratanakorn D, Nidhinandana S, Singhara Na Ayuddhaya S, Churojana A, et al. 2019 Thai guidelines of endovascular treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Thai Stroke Soc. 2019;18(2):52-75.

- Lokeskrawee T, Muengtaweepongsa S, Patumanond J, Tiamkao S, Thamangraksat T, Phankhian P, Pleumpanupatand P, et al. Prognostic parameters for symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke in an Asian population. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2017;14(2):169-176.

doi pubmed - Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, Larrue V, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352(9136):1245-1251.

doi pubmed - Trouillas P, von Kummer R. Classification and pathogenesis of cerebral hemorrhages after thrombolysis in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(2):556-561.

doi pubmed - Rohit S. Haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemicstroke. Radiopaedia. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/haemorrhagic-transformation-of-ischaemic-stroke. Accessed Nov 3, 2024.

- Shah S, Liang L, Kosinski A, Hernandez AF, Schwamm LH, Smith EE, Fonarow GC, et al. Safety and outcomes of intravenous tpa in acute ischemic stroke patients with prior stroke within 3 months: findings from get with the guidelines-stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(1):e006031.

doi pubmed - Choi HY, Cho Y, Kim W, Minn YK, Kang GH, Jang YS, Lee Y, et al. Analysis of mortality in intracerebral hemorrhage patients with hyperacute ischemic stroke treated using thrombolytic therapy: a nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea. J Pers Med. 2022;12(8):1260.

doi pubmed - Yaghi S, Willey JZ, Cucchiara B, Goldstein JN, Gonzales NR, Khatri P, Kim LJ, et al. Treatment and outcome of hemorrhagic transformation after intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2017;48(12):e343-e361.

doi pubmed - Phan TG, Chen J, Beare R, Ma H, Clissold B, Van Ly J, Srikanth V, et al. Classification of different degrees of disability following intracerebral hemorrhage: a decision tree analysis from VISTA-ICH collaboration. Front Neurol. 2017;8:64.

doi pubmed - Adams HP, Jr., Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE, 3rd. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41.

doi pubmed - The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581-1587.

doi pubmed - Rao NM, Levine SR, Gornbein JA, Saver JL. Defining clinically relevant cerebral hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for stroke: analysis of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke tissue-type plasminogen activator trials. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2728-2733.

doi pubmed - Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Davalos A, Ford GA, Grond M, Hacke W, Hennerici MG, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275-282.

doi pubmed - Fiorelli M, Bastianello S, von Kummer R, del Zoppo GJ, Larrue V, Lesaffre E, Ringleb AP, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation within 36 hours of a cerebral infarct: relationships with early clinical deterioration and 3-month outcome in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study I (ECASS I) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2280-2284.

doi pubmed - von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457.

doi pubmed - Larrue V, von Kummer RR, Muller A, Bluhmki E. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II). Stroke. 2001;32(2):438-441.

doi pubmed - Gumbinger C, Gruschka P, Bottinger M, Heerlein K, Barrows R, Hacke W, Ringleb P. Improved prediction of poor outcome after thrombolysis using conservative definitions of symptomatic hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43(1):240-242.

doi pubmed - Lokeskrawee T, Muengtaweepongsa S, Patumanond J, Tiamkao S, Thamangraksat T, Phankhian P, Pleumpanupat P, et al. Prediction of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: the symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage score. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(11):2622-2629.

doi pubmed - Krongsut S, Naraphong W, Srikaew S, Anusasnee N. Association of the type of intracerebral hemorrhage with serious complications and predictive factors for hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolytic treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Southeast Asian Med Res. 2024;8:e0186.

- Whiteley WN, Emberson J, Lees KR, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, Brott T, et al. Risk of intracerebral haemorrhage with alteplase after acute ischaemic stroke: a secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(9):925-933.

doi pubmed - Childress JF, Childress MD. What does the evolution from informed consent to shared decision making teach us about authority in health care? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E423-429.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.